Simple, deliberate, meditative--these are the qualities that dominated “River-Mouth-Ocean: Explorations in Afro-Asian Futurism,” presented this past weekend at Links Hall by choreographers Peggy Choy and Onye Ozuzu. The theme of water united the two halves of the program, one flowing into the other with an intermission separating the works of each choreographer. Themes ranging from ecology and Caribbean ocean mythology to bioluminescence and female solidarity lent a heady tone to the evening that was sometimes elucidating, sometimes mystifying.

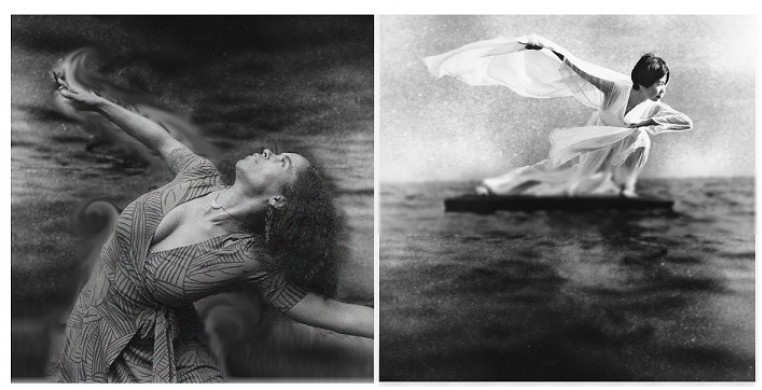

Choy opened her half of the program with “Wild Rice,” (premiere) a poetic lament to the dwindling presence of wild rice along Wisconsin’s Bad River. Her mesmerizing solo performance, set to a poem by Ruth Margraff, with a gently pulsating electronic score by GW Rodriguez, transmitted emotional depth and dramatic intensity with minimal movement, every gesture, every breath fine-tuned and focused. The utter clarity of a raised knee, a flexed foot, or undulating arms was quite wondrous and took on heightened importance in her purposeful execution of the sculpted phrases. Choy punctuated her slow, even progression across the stage with a startling percussive exhale, accenting an otherwise continuous flow, her gestures occasionally intersecting with the literal meaning of the poem. Superbly costumed in Cozbi’s drapey, saffron-colored culotte dress and diaphanous scarf, she could have been the incarnation of wild rice herself, an ethereal river goddess overseeing the last vestiges of life as we know it. Choy’s authority as both dancer and choreographer, combined with the substance of the spoken poem, opened the program with an intriguing perspective on how dance could intersect with ecological consciousness-raising.

Choy’s “Walk The River” (premiere) used equally minimalist movement to propel solo dancer Ozuzu on a slow-motion diagonal trajectory, performed in opposition to the rapid alto saxophone arpeggios of John Coltrane. The monotony of the underwater trudge was broken only briefly--once by a backwards summersault into animation that promised structural variation but quickly returned to the thematic stasis of the diagonal journey--and once by a puzzling series of disembodied facial expressions, indicating alternately surprise, pleasure, disbelief, horror, and grief. Here, minimalism was less effective, as the cerebral nature of the work didn’t offer enough physical structure to sustain interest.

“Ocean Woman” and “Cup of Water” comprise two excerpts from Choy’s larger work, “Thirst,” (2014), here superbly danced by two of Choy’s New York company members, Ai Ikeda and Lacouir Yancey. The combined solo and duet segments draw from a piece of Caribbean history in the 1880’s, when a group of African American men sailed to the island of Navassa in the Caribbean Sea to mine guano, working under brutal conditions. The dance depicts one mine worker’s dream of the mythical sea goddess, Green. The tiny Ikeda’s bird-like twitches and hand flutters contrasted with seductive torso waves and hip isolations. Afro-Caribbean turning leaps and punching leg jabs mixed with martial arts movement and flaring skirts. Yancey’s massive strength brought athletic hand stands, aerial cartwheels, and breakdance floor spins to his character of the thirsty mine worker. The excitement of their dancing was all too brief and, sadly, absent from the rest of the program.

After intermission, the audience was invited to tour the stage, where two life-size white plaster cast sculptures, created by Marie Ellsworth, now dominated the space. Their hollow interiors faced outward, showing the back-side imprint of a female torso, one standing upstage, the other reclining in a semi-fetal position diagonally opposite. They inspired curiosity and anticipation of interplay between dance and sculptures. Instead, Ozuzu’s solo for herself, “Make Wake,” paid them little heed, but rather, used the stationary forms as a reference point, a kind of visual commentary for her sensual exploration of her own body, as if she had emerged, newly-hatched, from their shells.

In a prelude, Ozuzu, dressed head-to-toe in body-snug whites to accentuate her curves, and balancing a white plaster bowl on her head, made a slow progression into the audience, where she offered the bowl to an unsuspecting child. In an awkward non-verbal exchange, she encouraged him to tip the bowl to her mouth to give her a drink of water. Her return to the stage combined naturalistic movements of rolling and stretching on the floor, sensual isolations of chest and hips, and a locomotor progression of child-like exploration that built to a climactic exorcism of Ozuzu shrieking repeatedly and retreating offstage.

Intellectual constructs can become catalysts for creative discoveries, or they can bog down the creative process with paradigms that get in the way of theatrically viable choices. In “Make Wake,” and the ensuing solo, “Glow In Deep Darkness,” performed by Choy, the latter was the case, where good ideas drowned in repetitive, everyday movement that never took off to the next level of compositional depth or originality.

The concert concluded with Ozuzu’s “Seven,” performed admirably by the energetic women of Ayodele Drum and Dance, along with Ozuzu.