By Sid Smith

Is a work of art ever really finished?

That question floated gently in the air during the latest installment of the Moving Canvas endeavor, a program Wednesday (April 16) at the Chicago Artists' Coalition at 217 N. Carpenter St. The objects on display as part of the Coalition's Hatch Project are seemingly complete visual objects--though their placement in the gallery and relationship to one another, and how that changes depending on the physical location of the viewer, are part of what curator Alexandria Eregbu is exploring. Even fixed physical objects can be altered by time and space.

Choreography, of course, embraces time as a function of the work itself--there is no precise atomic moment when you can grasp ahold of a work of dance and say, "Voila. This is the art." Like theater, it moves inevitably through time and changes, however slightly, with every performance. Blink, and one moment of a dance is gone forever.

So where does the essence of a work of dance lie? Is it ever really a fixed object or is it an ever-evolving force, almost its own bio-organism, open to action and reaction from its audiences?

Benjamin Holliday Wardell and Michel Rodriguez Cintra are the two agile, acrobatic dancers who combine to perform for the Nexus Project in an experiment that by itself explores this permeability and fluidity challenging the classic idea of rigidly complete art. They commissioned 12 choreographers to devise brief duets, but then the dancers took these works, isolated snippets from them and then remixed and re-ordered the excerpts however they wished. The dancers, as it were, snatched the baton from the hands of the choreographers and commandeered the conductor's podium.

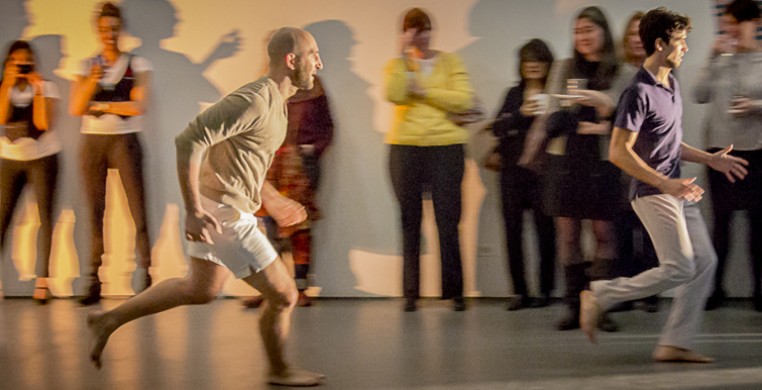

Enter Wednesday's Moving Canvas, which took this yet another step forward, or at least into a fascinating side alley. Wardell and Cintra performed a duet, made up of discrete sections, and then the audience, guided by host Zachary Whittenburg, discussed it, took it apart and suggested revisions that eventually reshaped the dance. After a brief break, the dancers then performed the audience's version so observers could assess their own handiwork.

"There Is No Spring in Cuba," in its original form, began with Wardell and Cintra lying prone, as if on a beach, to the accompaniment of their own recorded dialogue about the differences between spring in Wardell's native U.S. and Cintra's native Cuba. They eventually rose, to vigorously dance throughout the exhibition area, gently moving observers out of the way (and even briefly partnering with them) to a varied sound score that included vocalist Nina Simone. Near the end, an umbrella frame shorn of its fabric became a prop for Cintra, whom Wardell followed and then impishly baptized by dropping fistfuls of pebbles borrowed from one of the nearby works of art.

The mood was buoyant and carefree, the dancers smiling throughout, a mood an early audience commentator labeled childlike and playful. He described their interaction throughout the crowd as "peekaboo-esque." Two kids having fun at springtime.

But that overriding character, that seeming zeitgeist of the piece, was not to last. Bit by bit, section by section, revision after revision, Whittenburg and the audience essentially recast the piece, reshaped it and unleashed its somber underbelly. Someone urged that the opening dialogue be moved to the end of the piece and that the dancers stand erect while it was broadcast. The beginning thus became the ending. Meanwhile, someone requested that Cintra's insouciant solo to the Simone be more "smelly, dirty," while the umbrella section, it was urged, become more pronounced in its musical underpinnings. Instead of just walking, Cintra was urged to dance.

And it was decided that the fun-loving, cat-and-mouse play of the dancers, chasing each other around the space, would be given a darker hue, more predator and prey than playmates.

Victory for art by committee: All of these revisions made the dance more focused, direct and powerful. Instead of muddying and illogically re-ordering the work of meticulously planned artistry, the crowd's approach proved more coherent and focused in terms of exploring the content and theme of the piece. The original title, though changed to "Hurricane Season," actually made more sense.

Cintra speaks in the recorded dialogue of the absence of spring in Cuba, of its arrival not as floral rebirth but as harbinger of hurricanes. There's a gloomy philosophical underpinning of despair here beyond the seasonal comparison, of course. By relocating the dialogue to the finale, by coloring the interaction with tension and menace, by peppering Cintra's solo with "smelly, dirty" details, the work was dramatically altered from one about two Chicago friends enjoying an early spring day to one of layered philosophical conflict between optimism and determinism, rebirth and oppressive gloom. Spring is climactically a delight--but is it merely a flash of false hope?

The audience by no means got sole credit. Wardell explained that the smoother, more confident flow of the second rendering partly stemmed from the dancers' newfound experience navigating the crowd and the space, enabling a less tentative performance.

But that collaborative complexity doesn't alter the conclusion: Dance is a living, breathing, malleable force, especially in site-specific locales, where audiences are asked to participate. It can be a frozen creation of a single, great choreographic maestro, to be sure.

But it can also be a living organism, inviting, welcoming and benefiting from the insights of a community, who are likely to be all the more invigorated by joining the process.