Superb programming can expand both the heart and mind, which is exactly what Hubbard Street Dance Chicago’s Spring Series (Harris Theater, March 12-15) did Thursday night. A program so richly designed made for an exhilarating ride, so much so, you might even find yourself out of breath by the time I Am Mister B’s narrator tells you it’s over. Luscious dancing--the company never looked better--ignited works by four choreographers, each distinctive in unique ways that combined to make for a captivating study in themes and variations. Divided into three discrete segments, the program worked its magic with a startling combination of movement and sound, and the ever-evolving artistic chemistry of the dancers.

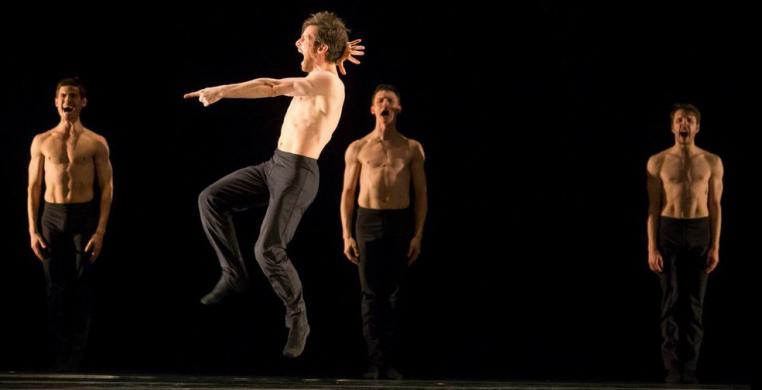

The first section gifted us with a second opportunity to take in all the wonders of Juří Kylián’s yin-yang pieces, Sarabande (1990) and Falling Angels (1989). Performed back-to-back without interruption, each piece incorporates live sound. Sarabande asks its six men to whoop, holler, grunt, breathe audibly, rub squeaky fingers on the floor, rattle shaking hands (who knew they made such sound?), and otherwise use their bodies to make tactile noises. A spirit of macho bravura alternates with abject fear in split-second timing, setting the tone for comedy. On second viewing, however, the poignancy of vulnerability also comes through in Kylián’s movement world, one that is driven by raw nerves and gut impulse. The sporadic insertion of recorded Bach Partitas for solo violin sustains an undercurrent of pathos in all the sturm und drang of action. There is no artifice or refinement to be found in shirts pulled up over faces and pants hugging ankles to reveal the naked skin of chests and legs. Kylián’s unconventional movement phrases rely on high-stakes movement drama. Hands touch their own bodies, exploring, embarrassed, caressing, as if discovering themselves for the first time. Drastic inversions of spinal arches and contractions, sudden thrusts to the floor, and bone-rattling vibrations explode into ecstatic flight. The choreography demands that dancers reach extremes in shape, energy, and speed, resulting in an emotional truth that tells its own, non-narrative story.

Third Coast Percussion

The eight women in Falling Angels, fierce and determined in a design wonder of movement geometry, managed to create the illusion that the floor beneath their feet was itself in motion. Third Coast Percussion, live on stage with drums and mallets, produced gamelan-like layers of rhythm and tonal variations that built excitement and suspense in the dancing. Here, too, hands touch their own bodies, cover mouths and faces, whisper “shh,” but it is part of an elaborate port de bras of bold, punctuated gestures that could be a secret sign language of elbows, wrists and shoulders. Dressed in short black body-suits with bare legs, these athletic women form a human train, shoulder to shoulder with linked arms that become a kind of railway track. Propelling forward in a mesmerizing unison sequence of forced arch pliés, extensions and relevés, their deliberateness gives way to a febrile flurry. Taught, on alert, anxiety hovering in the build-up of drumming intensity, the women pull the fabric of their body-suits out from their stomachs as if catching something from within, then blow kisses and wave good-bye.

Third Coast Percussion

The eight women in Falling Angels, fierce and determined in a design wonder of movement geometry, managed to create the illusion that the floor beneath their feet was itself in motion. Third Coast Percussion, live on stage with drums and mallets, produced gamelan-like layers of rhythm and tonal variations that built excitement and suspense in the dancing. Here, too, hands touch their own bodies, cover mouths and faces, whisper “shh,” but it is part of an elaborate port de bras of bold, punctuated gestures that could be a secret sign language of elbows, wrists and shoulders. Dressed in short black body-suits with bare legs, these athletic women form a human train, shoulder to shoulder with linked arms that become a kind of railway track. Propelling forward in a mesmerizing unison sequence of forced arch pliés, extensions and relevés, their deliberateness gives way to a febrile flurry. Taught, on alert, anxiety hovering in the build-up of drumming intensity, the women pull the fabric of their body-suits out from their stomachs as if catching something from within, then blow kisses and wave good-bye.

Grouping two smaller pieces together for the second program segment focused attention on the subtle poetry and exquisite emotional detail of Alejandro Cerrudo’s female duet, Cloudless (2013), and Crystal Pite’s male solo, A Picture of You Falling (2008). As with Kylián’s work, each of these pieces pioneered uncharted waters with refreshingly original, unconventional movement and a riveting use of sound.

Simplicity of line and gesture characterized Cerrudo’s Cloudless, as Ana Lopez and Jacqueline Burnett began their duet with a moving gallery of human Rorschach imagery. Nils Frahm’s quietly penetrating score forms an echo canyon for the movement. Alternately mirroring, entwining, and echoing each other, a gentle portrait of two women and their relationship evolves. Slow, effortless weight shifts leverage the women’s bodies on each other in a series of elegant lifts. Intimate to the end, simply gorgeous dancing unlocks the emotional core of the piece.

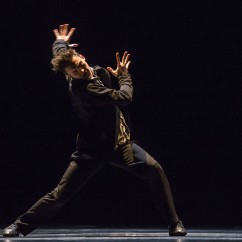

"This Is You Falling"

Pite combines her own voice and text with mechanical sound effects in A Picture of You Falling (company premiere). Jason Horton, in a stunning performance as human/machine, seems to be battling his body in a contentious war with gravity. Dressed in suit coat and slacks, he resists and falls repeatedly in a mind-boggling variety of constricted moves that would appear to be producing the ratchet clicks, gear shifting, squeals, bangs and pops of a struggling motor vehicle. “This is you falling,” Pite’s voice calmly intones. He falls, picks himself up, un-kinks body parts. He is a jumble of himself. When Pite says, “This is the sound of your heart hitting the floor,” and he falls once more, we are looking at the soul of a broken man, and yet both voice and movement are delivered dispassionately. The emotional impact is immense because it is transmitted through the combination of extreme force, contorted isolation of body parts, the abrasive sound of mechanics gone awry, the total absence of emotionalizing, and the speaker’s detached directives. “Take three steps back,” she says, “one, two, three. Then you stop, look back.” He does. She repeats, he complies, until she ends the piece with, “This is how it ends,” in a despairingly existential commentary on life that resists further commenting on itself.

"This Is You Falling"

Pite combines her own voice and text with mechanical sound effects in A Picture of You Falling (company premiere). Jason Horton, in a stunning performance as human/machine, seems to be battling his body in a contentious war with gravity. Dressed in suit coat and slacks, he resists and falls repeatedly in a mind-boggling variety of constricted moves that would appear to be producing the ratchet clicks, gear shifting, squeals, bangs and pops of a struggling motor vehicle. “This is you falling,” Pite’s voice calmly intones. He falls, picks himself up, un-kinks body parts. He is a jumble of himself. When Pite says, “This is the sound of your heart hitting the floor,” and he falls once more, we are looking at the soul of a broken man, and yet both voice and movement are delivered dispassionately. The emotional impact is immense because it is transmitted through the combination of extreme force, contorted isolation of body parts, the abrasive sound of mechanics gone awry, the total absence of emotionalizing, and the speaker’s detached directives. “Take three steps back,” she says, “one, two, three. Then you stop, look back.” He does. She repeats, he complies, until she ends the piece with, “This is how it ends,” in a despairingly existential commentary on life that resists further commenting on itself.

"I Am Mr. B"

Gustavo Ramirez Sansano’s I Am Mr. B (world premiere), completes the final program segment with a joyous homage to George Balanchine, whose ballet, Theme and Variations (1947), was a favorite work of Sansano’s to perform when he was a ballet dancer. Like Balanchine’s ballet, it is also set to Tchaikovsky’s Third Suite for Orchestra in G Major (op. 55, 1884). In paying tribute to “Mr. B,” Sansano hopes to “keep the energy and feeling of that piece alive.” As such, it is a raucous celebration of dance and life that demands of its twelve men and women, all identically dressed in Mr. B’s personal choice of black slacks, white dress shirt with a string tie, and navy blazer, to pull out all the stops, which they do, and then some! Sansano makes no pretense of imitating Balanchine’s choreography, but rather the artistic color and life with which the master infused his dance canvas. The stage, dressed in a canopy of deep blue period-style theater drapery and rows upon rows of curtains, suggests the elegance of ballet from a bygone era, but the dancing is 21st-century theater all the way with plenty of mime, spoken text, and visual high-jinks. At the very top, all the dancers introduce themselves together, saying “I am Mr. B!” One dancer/narrator steps out and, speaking directly to the audience, offers an endearing capsule of Balanchine history, which accelerates and devolves into a high-speed chase to the finish of dancers, curtains and drapes parting and closing, impossibly intricate footwork, and controlled stage pandemonium. The crux of Sansano’s tribute is his emulation of Balanchine’s revolutionary internalization and melding of the musical score into the fiber of the choreography and the spatial design of movement patterns. A consummate musician himself, Balanchine orchestrated his dancers, just as Tchaikovsky used different instruments to carry the complex melodies and rhythms of his music with different musical “voices” among the orchestral instruments. Sansano succeeded magnificently in making an orchestra of his dancers, with attention to the detail and nuances of the music reflected in ingenious ways through a movement style all his own. You could literally see the music happening in the dancers’ bodies and in the trajectories of their paths across the stage. Tchaikovsky wouldn’t have known what to make of this wild abandonment to raw movement, but my guess is Mr. B would have been proud.

"I Am Mr. B"

Gustavo Ramirez Sansano’s I Am Mr. B (world premiere), completes the final program segment with a joyous homage to George Balanchine, whose ballet, Theme and Variations (1947), was a favorite work of Sansano’s to perform when he was a ballet dancer. Like Balanchine’s ballet, it is also set to Tchaikovsky’s Third Suite for Orchestra in G Major (op. 55, 1884). In paying tribute to “Mr. B,” Sansano hopes to “keep the energy and feeling of that piece alive.” As such, it is a raucous celebration of dance and life that demands of its twelve men and women, all identically dressed in Mr. B’s personal choice of black slacks, white dress shirt with a string tie, and navy blazer, to pull out all the stops, which they do, and then some! Sansano makes no pretense of imitating Balanchine’s choreography, but rather the artistic color and life with which the master infused his dance canvas. The stage, dressed in a canopy of deep blue period-style theater drapery and rows upon rows of curtains, suggests the elegance of ballet from a bygone era, but the dancing is 21st-century theater all the way with plenty of mime, spoken text, and visual high-jinks. At the very top, all the dancers introduce themselves together, saying “I am Mr. B!” One dancer/narrator steps out and, speaking directly to the audience, offers an endearing capsule of Balanchine history, which accelerates and devolves into a high-speed chase to the finish of dancers, curtains and drapes parting and closing, impossibly intricate footwork, and controlled stage pandemonium. The crux of Sansano’s tribute is his emulation of Balanchine’s revolutionary internalization and melding of the musical score into the fiber of the choreography and the spatial design of movement patterns. A consummate musician himself, Balanchine orchestrated his dancers, just as Tchaikovsky used different instruments to carry the complex melodies and rhythms of his music with different musical “voices” among the orchestral instruments. Sansano succeeded magnificently in making an orchestra of his dancers, with attention to the detail and nuances of the music reflected in ingenious ways through a movement style all his own. You could literally see the music happening in the dancers’ bodies and in the trajectories of their paths across the stage. Tchaikovsky wouldn’t have known what to make of this wild abandonment to raw movement, but my guess is Mr. B would have been proud.