Joffrey Ballet’s “Unique Voices” presents a stellar showcase for both the company’s unique voice, and for the distinctive choreographic voices represented in a provocative program of three contemporary ballets, all Joffrey premieres. The dancers’ versatility and strength in ranks are in abundant evidence in all three pieces.

Stanton Welch’s “Maninyas” (1996), originally choreographed for the San Francisco Ballet, infuses the emotive gestural vocabulary of modern dance into the classical ballet idiom with exhilarating freshness. Both lyrical and abrupt, movement motifs of wide second-position pliés, contracted Giocommetti-like torsos, and inverted arms flinging v-shaped overhead, hands and wrists surrendered in supplication to something beyond, resurface throughout the several movements of Australian composer Ross Edwards’ lush “Maninyas Concerto for Violin and Orchestra.” Sharp, pulsing elbows, hands covering eyes, and flexed feet reflect the taught, heightened urgency of the solo violin. The piece has the feel of constant flight, painting the stage in a water color palette of five couples, color-coded in purple, red, blue, green, and brown. Dancers enter the stage running through three huge gossamer panels, the fabric caressing their bodies like silken veils as they flow in and out of couplings, trios, and full ensemble sequences. The set and costumes, designed by Welch, complement the fluidity of the choreography with a movement of their own, the women’s calf-length dresses swinging and swaying to drape and reveal in understated seductiveness. Each of the five women shone with distinctive mood and style. Amber Neumann, one of the younger dancers commanding increasing attention, brings special sensibilities to the contemporary idiom in a brief solo of dips to the floor, spinal arches, and flexed feet. In a climactic finish, the luminous fabric panels drop with the suddenness of a boom, the dancers glowing in golden light against the black void of space behind them.

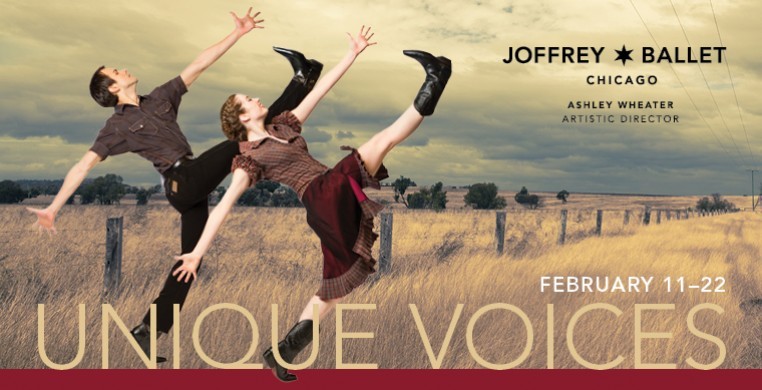

If you love Johnny Cash, you will love James Kudelka’s “The Man In Black” (2010), an homage to the singer’s gritty country and western style and bittersweet musical narratives. The six songs, danced by a quartet of three men and a woman, all in cowboy boots, riffed on line dance, square dance and step dancing, with a recurring theme of a bold group strut in circular sweeps of the stage, punctuated by lifts and heel scuffles. Simple in concept, the piece varied between movement generalization of the musical mood and a more literal relationship between the music and dancing, where lyric, gesture, and storytelling come together. It is a slight piece, pleasant in its casual affect and country ambience, and a faithful tribute to the music and the man, but of limited scope in structure and choreographic inventiveness.

Parody is the offspring of both passion and cynicism. If Alexander Ekman’s “Tulle,” which both lampoons and rhapsodizes classical ballet, had parents, they could have been Jonanthan Swift and Dante. Without the abiding parental love that must embrace it’s whole, parody can devolve into cheap sarcasm, but Eckman’s passion and respect for ballet ultimately transcend “Tulle’s” ridiculousness, and transform it into something approximating abstract art in motion. Ironically, it is in the overwhelming anonymity of the corps de ballet regimen--seemingly hundreds of identical women in white tutu’s and squadrons of men dressed as princes in white tights and sparkling tank tops--that the company’s collection of unique individuals really comes across. One of the ways Eckman achieves this effect is by engaging the dancers’ voices, both in recorded voice-overs and projected video clips, talking earnestly about ballet and what it means to master its discipline, while the dancers on stage are going through their paces. When we hear the dancers’ live, onstage vocalizations, boisterous and surprisingly rowdy as their maniacal ballet regimen accelerates to absurd intensity, these ethereal automatons become living breathing human beings. Into the mix, we get a brief Ballet Appreciation 101, complete with Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette on an upstage platform.

Prodigious technical virtuosity is a prerequisite for any good satire. In “Tulle,” a parody of Swan Lake includes the company’s women whistling the famous Tchaikovsky melody, but not without Victoria Jaiani’s exquisite recap of her recent portrayal of Odette. A circus segment satirizing the spectacle of the pas de deux has April Daly and Miguel Angel Blanco mock-showing off for all they’re worth to the fake cheers and applause of an on-stage audience, but what splendid dancing!

Eckman’s set design of rectangular panels, used for the projections, becomes an illuminated decor of blue dots in the final section, where the military precision of standard ballet etudes transforms the patterns of mass group movement into a resplendent release of energy and design, something rather magnificent and awe-inspiring, transcending the seven goofy circles of Dante-esque Purgatory to the uniquely sublime Paradiso that the best of ballet delivers.

Lynn Colburn Shapiro