For this next Moving Dialogs: Global Exchange event onThursday, May 1st at Soham Dance Space, Dr. Ananya Chatterjea offers some thoughts to inform the conversation:

Moving In/Out of “Tradition”

How does Indian cultural production locate itself in the US? It often seems to me that the reception of much of what is described in programming and marketing as “ethnic dance” (translation: dances from “other/non-white” cultures, whether they are made in the US or not), as well as the broader spectrum of “ethnic culture”, is overdetermined by lens that have been in place for many years, but now more complicated by global industry.

4/14/14: A blog post from Jezebel, a popular and generally quite sophisticated women’s website, draws attention to how bindi’s were the new fashion accessory at the Coachella Festival. “Another year, another Coachella, another trend mired in cultural appropriation. It’s the true circle of life. You can almost watch the fixed gears of hipster logic grind: Now that Native American headdresses are offensive, we need to snatch some cool novelty from another culture. And so it came to be that bindis were a hit at Coachella.” (http://jezebel.com/take-that-dot-off-your-forehead-and-quit-trying-to-make-1563531208)

The widespread availability of cultural symbols such as bindis, now sold in multiple shapes, sizes, and colors on ebay and Amazon, simply reveal globalization’s drive towards the marketing of access. The neo-liberal market sells all and ships to our home even. And we can all rock those bindi’s, during Halloween, during a music festival, every day, and demonstrate how “global” we are. But then, what is the nature of that access that is created? What are the markers of our increasing understanding of brown bodies dancing an aesthetic that might not fit into the mainstream understanding of good line and technique?

Celebrated Tanztheater choreographer Pina Bausch created Bamboo Blues in 2007. It toured Europe and America in 2007-08 and then again in 2012. The piece draws inspiration from Bausch’s visit to Kolkata, incorporates classical and contemporary Indian music by artists such as Sivamani and Trilok Gurtu, and flashes of images from Bollywood films projected on the back wall, and features Kuchipudi dancer Shantala Sivalingappa. The piece is described as presenting “fragments” from Indian life, and admittedly not at all about India, but rather about Bausch’s exploration of human experience. The piece did not do so well in London, where the dance scene is saturated with a range of concert performances located in Indian dance. Louise Leven, reviewing it for The Telegraph, remarked on what felt to her to be the “touristy” note in the work and commented that: “If a white British dancemaker made a purely ornamental piece about contemporary Bengal that didn’t touch on colonialism, poverty or pollution, they would be hung out to dry” (July 4, 2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/dance/9376806/Tanztheater-Wuppertal-Pina-Bausch-Nefes-and-Bamboo-Blues-Seven-magazine-review.html).

The reception in the US was quite different, and much more friendly. Writing on her website dedicated to arts and dance criticism, Dancing Perfectly Free, in 2008, Evan Namerow, describes the piece as a “rich and visually stunning work” that “offers myriad episodes – covering a broad array of emotions – that are the result of Bausch’s research in India” (Dec 18, 2008, http://dancingperfectlyfree.com/2008/12/18/pina-bauschs-bamboo-blues-at-bam/). Alistair Macaulay, New York Times dance critic, was a bit more critical but still rather respectful. He emphasizes the “dreamspace” choreographic mode of so much of Bausch’s work, but admits that Bamboo Blues feels like the dream of a European who has spent time in India but whose mind is mainly elsewhere” and as “toying coyly with India” (12/12/2008http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/13/arts/dance/13baus.html). What might these responses reveal about the place of Indian dance in these cultural contexts?

I bring up Bamboo Blues here, not to raise questions about Bausch’s choreographic brilliance, but to wonder about how India, elements of Indian culture, and snatches of Indian dance, broadly speaking, function in the Euro-American imagination. As a Contemporary Indian dance choreographer, it is impossible for me to not groan at the white male dancers who fold in the towels they are wearing around their waists, till they become loincloths. Or not to clutch at my seat when a woman enters wearing an elephant head. Both are moments from Bamboo Blues. I cannot help feeling that “Indianness” enters the sophisticated world of European contemporary dance almost in drag, through these old stereotypical elements, invoking, at least, a sense of excess. Or, as it has done since the days of early modern dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis’ Dance of Black and Gold Sari [1923], offering a backdrop for self-exploration from a different perspective, bringing in exactly as much “otherness” as the choreographer needs to de-familiarize the context, only to plunge back into self.

And then, there are some brilliant exponents of different classical Indian dance forms who were presented by the World Music Institute in New York City this April, organized under the theme, Dancing the Gods. Without denying the inherent spiritual foundation of Indian classical dance, is it time to ask how these dancers negotiate this spiritual expression with the contemporary urban contexts they traverse, frequent flier mileage coordinations, and theater fire codes that do not allow them to light the mandatory oil lamp in honor of the deity on stage? What kinds of access do we create when we invoke divinities in the current concert dance market?

The movement, tensions, and continuities between traditional, neo-classical, and contemporary forms in the Indian dance world play out in a global arena that is circumscribed by such forces. And, there is also, currently, a plethora of genuine opportunities through platforms—such as this particular Moving Dialog— where Indian dance, contemporary and classical, is being programmed and brought to the forefront. The challenge to choreographers, dancers, and thinkers who work in Indian dance is at least three-fold: (a) to create dialog and space for reflection within the field, so we might evolve, over time, conscious strategies to shape the field in our own terms; (b) hold on to the bases of our particular aesthetics and resist the pull to spectacularize it to match Euro-American notions of virtuosity and line; (c) and to remind ourselves constantly that historical structures that masquerade as “universal” are still culturally specific narratives, such that statements of rejection and differentiation by choreographers of postmodern dance of its predecessor, modern dance, and by choreographers of modern dance of ballet is particular to the US dance scene, and may not be part of other contexts.

We might alternatively reflect on how to frame the relationship between different practices and aesthetics in Indian dance, neo-classical, “folk”, contemporary, not through categoric binaries that have been thrust upon us, “tradition versus innovation”, but rather through tracings of continuities, resonances, and parallel aesthetic markings. It might also be productive to analyze the many layers of what goes in the name of “Tradition” and how this category of culture is mobilized to accomplish particular effects in different circumstances. We might ask: how do we understand the “tradition” of Indian classical dance forms, most of which were reconstructed during the nationalist cultural revival movement in India in the mid- to late- twentieth century? Might it be that when we muddle through these questions and how we position ourselves in this complex scenario, we are able to create the kind of access and critical reception we long for our audiences to have?

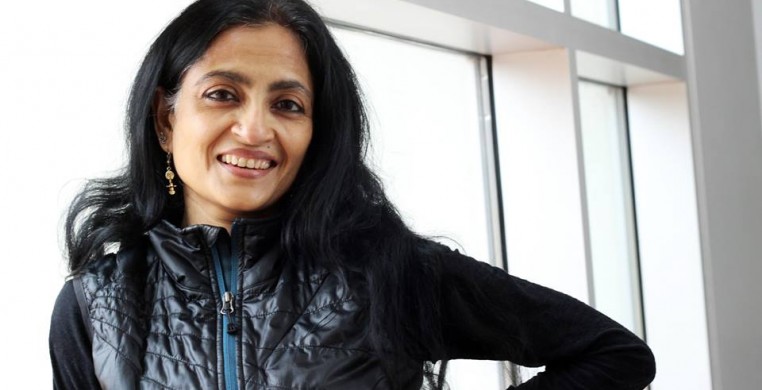

--Dr. Ananya Chatterjea

Dr. Ananya Chatterjea, Artistic Director of Ananya Dance Theatre, is a Contemporary Indian dance choreographer who creates works intersecting artistic process and social justice. She moderates the upcoming Moving Dialogs: Global Exchange event Moving In/Out of “Tradition” on Thursday, May 1st, from 6:30pm – 8:30pm at Soham Dance Space. Joining her will be Artistic Director of Toronto’s InDance and Wesleyan University professor Hari Krishnan and emerging local choreographer Anjal Chande, founder of Soham Dance Project. Curated by Baraka de Soleil. May Associate Curator Malii Brown. Produced by Audience Architects. This Moving Dialog is in union with Chicago Dance Month’s Open Doors event being held at Soham Dance at 6:00pm. Doors open at 5:45pm. space is limited. RSVP by clicking here.