Gutsy, brash, and intent on standing convention on its ear, Twyla Tharp started her illustrious career as a choreographer in 1965 with “Tank Dive,” a full 7 minutes of dance as minimal as movement gets, standing in second position relevé for the entirety of the pop song, “Downtown.”

This past Friday night, Tharp stood behind a podium on the Museum of Contemporary Art stage, impish in her slouchy jeans and sneakers, characteristic oversized glasses halfway down her nose and shaggy mop of now white hair, and launched into “Minimalism and Me.”

Commissioned by the MCA and premiering this past Thursday through Sunday, “Twyla Tharp: Minimalism and Me” is Tharp’s account of her early forays into the art of making dances, learning what it meant to be an artist from minimalist painters like Barnett Newman, Frank Stella, and Agnes Martin, whose studios dotted the Greenwich Village neighborhood where she took up residence in a fifth-floor walk-up after graduating from Barnard.

Venerated as one of the most significant dance innovators of her time, Tharp looks back to her earliest influences with the self-effacing humor of one whose perspective takes in a period in American art, literature, and dance that encompassed minimalism, conceptual art, and post-minimalism.

Using five of her company members to illustrate excerpts of works created from 1965-70, Tharp’s running commentary provides a context for understanding what she was trying to do, and which elements continue to drive her process today. In addition, her first-hand account of a pivotal moment in modern dance history lets us see where she eventually split off from from the Judson Church group that included avant-garde choreographers like Meredith Monk, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and David Gordon.

Tharp created “Re-moves” for inclusion in a multi-choreographer show at Judson in 1966. The point of “Re-moves,” she said, was “to repeat over and over and over. A dry concept!” Minimalism meant using walking and rolling on the floor, close enough to the brush the shoes of the famous dance critic Clive Barnes sitting in the corner. “It was shameless,” she quipped, describing the work as “less is more on steroids.”

In part two of “Re-moves,” the audience saw only one-half of the action. In part three, a huge plywood box limited the audience to only one-third of the action, and part four took place entirely inside the box, where the audience could see nothing. There were no curtain calls, and by the end, no audience. “It could be shocking,” she said, “but not entertaining.”

Next came post-minimalism, where In the fall of 1967, Tharp created “Generation,” from elaborate notes and diagrams of spatial patterns. Projections of Tharp’s notebook diagrams appeared on the back wall of the MCA stage. Her dancers demonstrated the convergence of bodies in the spatial design. She began “exploring movement with a vengeance,” still, the rule being “no virtuosity.” She began to explore unlikely sequence, breaking all the “no” rules, and incorporated fundamental human movement like running and jumping.

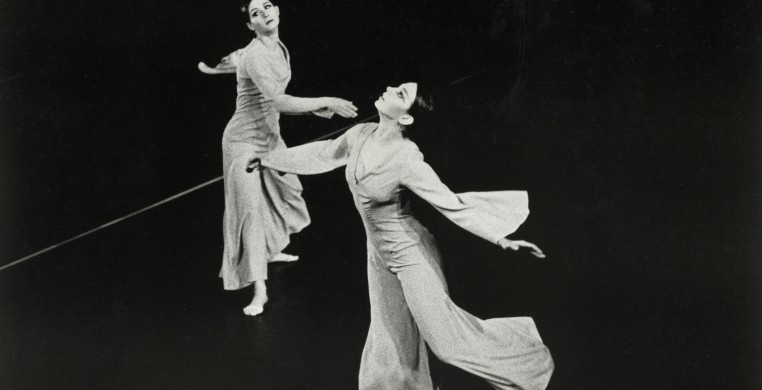

In 1968, she created “Medley,” introducing technically-based dancing with four distinctly different solos, recreated for the MCA audience by each of four distinctly different dancers. The first was precise , with sharp reflexes; the second “fast, faster, and fastest;” the third using phrasing for never ending fluidity of movement; and the fourth, “a powerhouse” of energy.

Continuing her attraction to the aesthetics of visual art, Tharp staged performances in the Met Museum’s Great Hall, where she posited that “dances were works of art,” letting the audience bounce off the dancers as they would off a canvas hanging on the gallery walls, “as they do in all exhibited art works.” Combinations of pedestrian movement merged with tap dance shuffles ball-changes, and ballet.

Between 1965 and 1970, Tharp created 20 works. She began seeing dance “as a commodity,” creating “Opus One,” which she credits as the real beginning of her authentic voice as a choreographer. “Opus One” explores the fugue, both in audible and inaudible movement, created by the dancers’ foot rhythms, hand clapping, body slapping, and flat-foot flops. Her characteristic easy swinging arms, flexed feet and hip swivels mixed with arabesque posés, all becoming part of a visual and auditory rhythm score, exemplified on the MCA stage by Tharp’s live crew.

“Dance is a simple business,” she said. “You go into an empty space and come out with a document of your existence.” Tharp gave her audience a taste of what that’s like, creating before our very eyes a brand new dance on John Selya and Matthew Dibble, two long-time collaborators and company members.

Seeing Tharp in action, her quick directives peppered with French, she gave us a small document of that existence to take home. That Tharp eventually left conceptual art behind in favor of a more ballet-based, technically-demanding choreographic palette doesn’t diminish the role her experiments with minimalism played in shaping her nascent understanding of process and aesthetics in the art of making dances.