The Joffrey Ballet continues its commitment to presenting narrative ballets with the Chicago premiere of British choreographer Cathy Marston’s “Jane Eyre” (2016), adapted from the 1847 romantic era novel by Charlotte Brontë, but re-imagined through the lens of 21st-century psychological fiction.

Opening the Joffrey’s final season at the Auditorium Theatre before relocating to the Civic Opera House next year, Marston’s adaptation cuts to the core story events in the novel, and yet finds in dance a stunning entryway into the world of Brontë’s writing. Through alternating literalness and abstraction in scenes that reveal Brontë’s early feminist leanings, she employs both “telling” and “showing” in an artistic approach that thoroughly integrates movement, set, costumes, lighting and music.

If you’ve read the novel, and loved it as I have for both its compelling story and brilliant writing, you may lament the absence of some quite wonderful moments and the over-simplification of plot. The trade-off is that Marston’s adaptation makes choices that not only make sense for dance, but capitalize on the unique capabilities of dance to unlock and reveal meaning in the text. And she does it with a choreographic freshness that captures character and relationship with spot-on physicalization of what in acting is called the "psychological gesture.” (Note: If you haven’t read the novel, and maybe even if you have, be sure to read the program notes before the curtain goes up!)

One of the most significant choices in this production is to condense the story telling with a reconfiguration of the novel’s linear time, opening act one mid-novel, with the single-most crucial dramatic turning point of the story. From this crisis moment, we see Jane’s life up until this point through her memory. Flashbacks in linear time sequence lead up to the same scene, repeated in act two, followed swiftly by an abbreviated denouement.

This choice notches up dramatic tension throughout the ballet in two ingenious ways. In terms of visual and emotional intensity, it starts right out the gate at a “ten," placing the audience squarely inside the explosive psychological reality of Jane's despair, pain and fear in the void of set and costume designer Patrick Kinmonth’s abstraction of the moors.

The visual abstraction of a vast and uninhabited landscape surrounding the literal storytelling that ensues sustains suspense with its looming presence, almost like another character, as a constant reminder that Jane’s life teeters on the edge of disaster at every turn. This abstraction stands in stark and poignant contrast to the period costumes and furniture that create a cloistered bubble of tenuous reality within that larger void, visually manifesting Brontë’s dichotomy of romanticism and psychological drama.

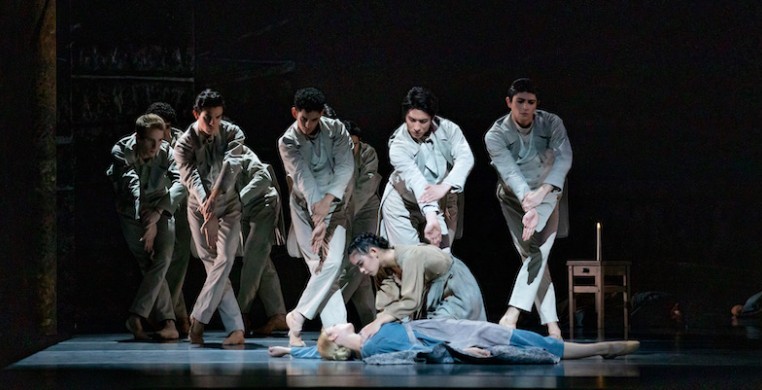

The other device Marston introduces so effectively in this opening scene is the Greek chorus of “D-Men,” Jane’s psychological demons, who reappear at crucial moments throughout the storytelling, contrasting Jane’s interior monologue with the external story action. Dressed in the formal attire of vests and tailcoats, they embody the clashing thoughts that render Jane temporarily helpless and at the mercy of St. John Rivers, the cleric who rescues her and nurses her back to health, stoically portrayed by Edson Barbosa.

The agitated violins and eerie clarinets of composer Philip Feeney’s original and compiled score fuel Marston’s piercing arms and legs, handstands and frantic lifts as Jane, exquisitely danced on opening night by Amanda Assucena, is blocked at every turn and tossed mercilessly in a sea of terror.

The D-Men also stand in for fate, death and destiny, crawling out behind movable tombstones from inside the upstage platform. Seated on top of the platform, the adult Jane witnesses herself as a child, danced by Yumi Kanazawa with heart-wrenching poignance, at the funeral of her parents. From this adult vantage point she relives her past with her repressive aunt (April Daly) and bratty cousins, (Yuka Iwai, Valeria Chaykina and Xavier Nuñez) and suffering through the punishing schooling of Reverend Brocklehurst (Temur Suluashvili). In a magical transfer of bodies, we see the young Jane morph into her adult self as the two dancers merge and separate, leaving the adult Jane to enter her career as teacher and tutor.

The highly-stated gestural signatures of the various characters begin with shapes in the arms and amplify through the spine, head, shoulders and legs to embody an entire being who is consumed by piety, power, flightiness, dominance, subservience or madness. It is a vocabulary that moves and powers its characters through space, from the literalness of prayerful hands to the abstraction of a giddy leap, and back again. Marston’s movement creates dramatic truth through the seamless blend of this highly impulsive abstraction of emotional gesture with a skilled and creative manipulation of the codified vocabulary of classical ballet.

And the Joffrey dancers deliver! Every role is nuanced and believable. Opening night leading roles of Edward Rochester (Greig Matthews) and Assucena’s Jane carried the day with movement dialogue that navigated the dips and turns of dominance, hesitation, passion, devotion and betrayal.

Especially notable in support roles were the limpid Helen Burns (Brooke Linford), Jane’s friend at the Lowood School; quirky Mrs. Fairfax (Lucia Connolly), the housekeeper at Thornfield; and the giddy Adele Varens (Cara Marie Gary), Jane’s pupil and Mr. Rochester’s ward. The surprise of the night was Christine Rocas, whose versatility shone in a breathtaking tour de force performance in the role of Bertha Mason, Rochester’s mad wife.

The bones of this story include major hallmarks of 19th century romantic fiction: a Cinderella rags-to-riches tale of deprivation with a happily-ever-after ending, and a heroine who resists temptation for the morally righteous choice of Christian virtue. Published in 1847 under Brontë’s pen name, Currer Bell, ostensibly to disguise her gender, Jane Eyre was revolutionary in several ways. It was the first novel written in first person from the point of view and in the voice of the fictional main character. Additionally, the protagonist is a strong-willed, intellectual, and self-actualizing woman who flies in the face of convention and presents a complex and layered expression of feminist rage and rebellion.

No one adaptation, whether in film, live theater, music or dance, can fully capture the breadth and depth of a novel like “Jane Eyre.” What we can hope for, however, is that the adaptation utilizes that medium optimally for its unique capabilities. Cathy Marston’s “Jane Eyre” may not have touched on some of the un-danceable aspects of the novel, but it went a long way toward implying them, and has given us a physical entry into the literary world of Jane Eyre that has captured much of the authenticity of characters and emotional intensity of Brontë’s writing.