When Coronavirus (COVID-19) hit, most educational institutions were directed to move in-person classes to remote, online learning platforms. At my institution, Kent State University, a lot of care was taken to ensure that the students were supported, and resources made available to them. But the dance faculty at Kent State had three days to transfer their studio-based technique classes to virtual dance classes and that mandate, for me, was accompanied by anxiety.

As a pre-tenured Black faculty member who experienced bias throughout my reappointment processes, I became fretful, knowing I would not be able to participate in activities that would augment my tenure dossier. And while my institution offered tenure-track faculty a courtesy extension on the probationary period leading to their mandatory tenure review, I wrestled with this offer, thinking about my past experiences, not wanting to relive the trauma of withstanding an additional review process. This gesture from my institution, an articulation filled with good intentions, did very little to provide any comfort as I continued to feel uneasy. I was positioned at the forbearance of those who embody privilege; those who may prefer my privation as they get to decide if I belong.

Being a Black faculty comes with challenges, especially when teaching in a predominantly white institution. Being a Black dance professor further amplifies those challenges, knowing the discipline was not as revered as those in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields. Maybe I was alone in thinking this, but I wondered if my institution would totally eliminate dance as a major. Let’s not forget that most Black dance professors work ardently while navigating micro-aggressions, discrimination and racial violence. COVID intensified persistent feelings of insecurity and discomfort. I had grown accustomed to overproducing, thinking that was the only measure of my value to the institution, while wondering if the dance major was at risk of being expurgated.

When classes went remote, I worried my work would not be seen. How would they know I was doing all that I needed to do and that I was deserving of tenure in this profoundly white, patriarchal culture? The tenure process at my institution asked that the initial evaluation of junior faculty’s work be done by colleagues. In predominantly white institutions, the colleagues of Black faculty are primarily white. That is not all cases, and surely not in all institutions. But what this does is allow for a process buoyed by evaluators’ biases. It provides excuses to reject faculty from marginalized communities; claim it’s “not a good fit” because of personal discord or by citing “poor student evaluations,” even though Black faculty continue to be at the mercy of the acerbic pen of white students; or simply not value the research or creative activities presented if they are not rooted in Eurocentric norms and aesthetics.

Yes, COVID gave me time to perilously ponder my path towards tenure and promotion.

Some Black dance faculty had other worries. Over Zoom, Dr. Kemal C. Nance, assistant professor of dance and African American Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, spoke about going remote. Dr. Nance explained that it didn’t really have a grave impact on his teaching. “COVID hit in a moment when I wasn't teaching any movement classes,” he said. “I was probably more prepared than my colleagues… I had already switched to doing stuff on Zoom. I just had to figure out how to make sense of the students’ choreographies without having to see them live. I think the thing I was most affected by was the isolatory nature of this pandemic and what that does to the spirit.”

Dr. Nance expressed that he had a conversation with himself, acknowledging that if he didn't have a smart device or a computer, he wouldn't have interacted with anyone for a very long time. He confessed that the pandemic intensified feelings of loneliness. “If you were alone, you were even more alone... It's almost like you were in a vacuum and I think that's impactful for Black dancers and Black artists, because this pandemic gets at the very mechanism we use for survival and the very thing that we do to get through adverse times.”

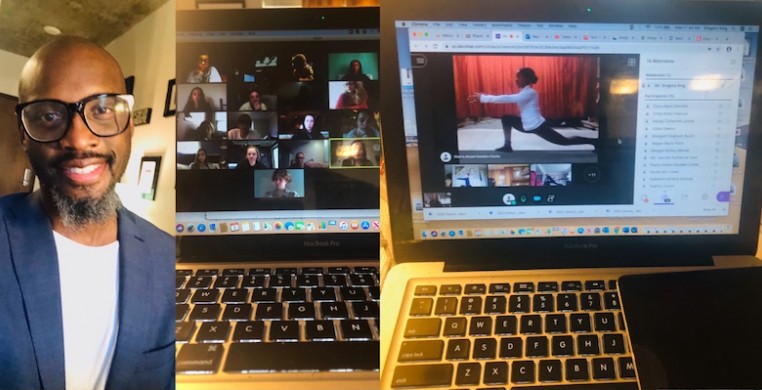

When classes went remote, I self-questioned, wrestling with how the dancers would actively participate. I knew online Horton technique classes were not optimal for engagement; still, I kept trying ... and trying. In the face of COVID-19, in addition to considering new methods of engagement, I employed diverse attitudes toward assessment because the importance of live class experiences had been replaced by technology. Whereas before, I had a rubric based on memory, anatomic correctness, demonstration of the technique learned and musicality, I knew an online format wouldn’t allow for accurate evaluations.

For that reason, I relied on interesting methods to evaluate the dancers: I implemented a writing assignment to assess their intellectual understanding of the movement information shared before classes went remote. I asked that they prepare and give an oral presentation of their career development plans, insisting they carefully contemplate dance post-college. This was also compounded by the reality that some students did not have access to spaces conducive to dance training. Some lived in rural areas with dodgy internet connections, while others were spending the quarantine in homes where they were charged with the task of assisting parents—who may or may not have been newly unemployed— with their siblings and additional chores from just being at home. So, as we scurried, attempting to become more efficient at teaching dance-related courses remotely, it became apparent that faculty and administration were not having critical and necessary conversations about best practices, keeping in mind conditions that may negatively impact some students.

Dr. Nance spoke about a rehearsal he had earlier that day, saying one reason it was so successful was because of the interaction—seeing the dancers in person, laughing, joking, and moving together. He added, “Even though they couldn't hug or hold each other's hands, it was nice just enjoying each other’s energies and spirit.”

The truth is, online learning is not new as it had its beginnings in the late 1900s. But teaching Afro-Caribbean, hip hop, tap and other jazz forms, modern dance techniques and ballet, professors may be encouraged to modify approaches, rethink assignments and adapt assessment simply because dance is a discipline that depends heavily on the students’ physical presence. But teaching online also afforded some Black faculty the opportunity to dig into their creative hampers, teaching old classes in imaginative ways, while allowing others to propose courses that may have had strong desires to explore.

Dance scholar Dr. Raquel Monroe interlaced her administrative duties as co-director of academic diversity, equity and inclusion at Columbia College Chicago with her pedagogy. In a Zoom chat, Dr. Monroe admitted that taking classes remotely due to COVID afforded her the chance to teach a class she had been preparing her entire career. Dr. Monroe spoke of her pro-Black, feminist praxis, using it as the framework for the class she conceived last fall. The course would be a study on how Black feminism has informed the Black Lives Matter movement. Dr. Monroe’s scholarship is as a theorist and a practitioner, giving her students context for looking at choreography as protest, choreography on the stage and screen, and choreography in the streets and on the social dance floor.

In a moment of euphoria, Dr. Monroe remembered how the value of the class was revealed, saying, “When the non-verdict of Breonna Taylor's murder was announced—and it happened minutes before my class was to happen—I walked in and said, ‘Apply the analysis. I'm going to put up a discussion board. You all …. apply the analysis. You're reading about stuff that happened in 1968 and we are in 2020; what is the difference? Apply the analysis! I'm not teaching today.’” She anchored with clapping hands, “And they did!”

It was a perfect example of how COVID may have offered Black faculty the chance to curate and harness our pedagogical power.

The pandemic has made me anxious in my journey towards tenure and promotion, but it also reminded me of the communities of Black love and Black access all around. And as we continue to share cartographies of our movement ideals, let’s stay energized, stimulating the narrative that Black dance professors teaching in a time of COVID continue to be resplendently resourceful in the academy and beyond.