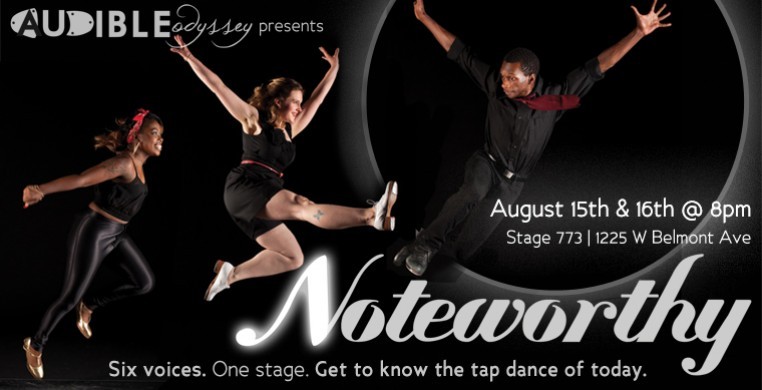

Take a houseful of virtuoso tappers from across the city, set them loose on six tap choreographers, and you get “Noteworthy,” Audible Odyssey’s intimate, inviting, all-inclusive pep rally for the art of tap dance held last weekend at Stage 773.

The emphasis is on something different. How far can you extend a rhythmic riff; how fast can the vibrating monologue of one foot speak to the other; how deeply can the heartthrob of soles touch the internal longings of the soul? In “Noteworthy,” six very different choreographers answered those questions in uniquely tap terms, but with sharp conceptual differences that beg another, more universal question: is looking at tap dance any different from looking at jazz or ballet or modern dance? Why, and why not?

As with any performing art, we appreciate technique in and of itself. We applaud the ballerina who stops the show with thirty-two fouette turns in the middle of a dramatic love story about a prince who falls in love with a swan. And we marvel at the extreme dexterity (pederity??) of the tapper who hits the ball out of the park with unbelievably complex rhythmic combinations, engineered through the instrument of shoes that make that oh-so-compelling click-clack sound, executed with mind-boggling neurological wiring. But without the fuller context of artistic form, whether abstract or narrative in concept, without choreographic elements of spatial design, effort, weight, and shape, and without that ineffable quality, feeling, that’s all it is: technique. We demand that our art “speaks” to us on an aesthetic level elevated from that of a circus act. Tap dance has traditionally had a foot in both the “circus” (the minstrel show, and later, vaudeville) and the concert dance or jazz music stage, and perhaps it is because of this duality that we tend to forgive tap dance when it is less than choreographically complete. We can enjoy it, more than with other dance idioms, for its sheer virtuosic element, both as dance and as music, since, in the unique case of percussive dance, the dancer is also both a musician and a musical instrument.

These are the waters Audible Odyssey seems to be navigating, with varying degrees of aesthetic pioneering. The most imaginative and sophisticated collusion of artistic concept and tap technique were Martin Bronson’s opener, "On The Line," and Zada Cheeks’ finale, "Diabolus." Both works addressed the musical integration of tap dance and instrumental score, utilizing spatial design and whole-body movement that was visually arresting.

In Bronson’s "On The Line," live music based on Ahmad Jamal’s song of the same name, brought the art of jazz and jazz tap to a thoroughly satisfying theatrical whole in which you sensed the dancers were part of the jazz combo, not dancing “to” the music, but part and parcel of its fiber, realized in space as a unity of visual and audible design.

Zada Cheeks’ "Diabolus" for three men and one woman captured the mood of Allyn Ferguson’s music in full, whole-body gestures, with each dancer “orchestrated” to individual instruments. Here, too, the integration of superb tap dancing and melodic score was seamless and thrilling to both hear and watch for the imagination Cheeks brought to the partnership. Cheeks’ riveting solo became a duet of drums and dancer that nailed rhythmic precision and revved up the excitement with indefatigable energy and joy, ending in an attitude penche that transitioned into a trio for Martin Bronson, Tristan Bruns, and Jessica Chapuis, who branched off on her own to a splendid trumpet solo. Diabolus truly raises the bar for tap choreography, born of musical sensitivity, compositional integrity, and inspired performance.

Jenna Deidel’s "This one’s for you." is a narrative piece that explores relationship through story-in-tap. We could almost hear the interior monologue each character was thinking in the very tone, rhythm, and attack of the tapping, an intriguing idea, if somewhat too long and repetitive in its unfolding. Phil Brooks made a sympathetic character as the moody lover. The arc of emotional transformation in the two main characters from anger and resistance to forgiveness and acceptance was not sufficiently supported through believable dramatic development, but that’s a challenge of new territory for tap dance, and Ms. Deidel should be lauded for sustaining clear storytelling in the tap idiom.

Star Dixon’s "I Love..."was an endearing tribute to her first teacher, her love for tap dancing, and the power of love. Spoken text by Ayinde Cartman interspersed with danced segments. Cartman’s writing was filled with great words, like “tell the butterflies in your stomach to make room,” but it wasn’t clear if the spoken text was a continuation of the piece, or a separate species unto itself. The writing--poetic, with striking imagery and strong voice--suggested the possibility for further collaboration and integration into the body of the danced segments. The piece as a whole, while beautifully danced, was a bit disjointed and could benefit from structural tightening.

Jumane Taylor’s "Supreme Love" showcased the choreographer’s unique style and talent, with his own special take on tapping to rap. Whatever the program note said, the choreography didn’t deliver a clear theme, other than the lyrics to the rap, but the dancing was so emotionally intense and personal, it didn’t matter. The speed of Taylor’s tap vibrations was astounding. All we had to do was watch it happen, and that was enough!

Melissa Reh’s "Both Sides" had a light tap touch set to Joni Mitchell and Arcade Fire. This story-in-tap of a relationship that heals over time needs more character development through movement to be believable, but again, kudos for starting the journey. The piece used space with some imagination, capitalizing on social dance idioms that really moved, but the storytelling relied on facial drama more than it needed to.

All told, “Noteworthy” lived up to its title, with tap dancing that speaks to us through its medium about what matters, and aspires to transcend technique to achieve something new and different.