In Director Robert Lepage and choreographer Guillaume Côté’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the prince of Denmark never utters a word. Their innovative exploration of the play is a collaborative integration of movement, multiple dance genres, music, visual design and theater. The U.S. premiere will take place at Chicago’s Harris Theater Nov. 23-24, 2024.

“To be or not to be” are some of the most famous words in the history of theater. What is “Hamlet” without his famous soliloquy? But Côté, principal dancer of the National Ballet of Canada, transcends the spoken word in a minimalist distillation of text through gesture. “Minimal movement patterns can communicate,” Côté said in a recent telephone interview with SeeChicagoDance. “Micro-movement can convey huge amounts of emotion.”

Côté said he choreographed line to line, the artistic team exploring the text in collaboration. “We started with small tiny movements,” he said of the group improvisation sessions in the rehearsal process.

The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark; Photo by Sasha Onyshenko

The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark; Photo by Sasha Onyshenko

Unlike traditional story ballets where mime provides much of the narrative glue in the storytelling, the co-directors wanted no mime. They also chose to avoid the traditional story ballet convention of interrupting the narrative flow with choreographic variations that show off the technical virtuosity of the lead dancers and sprinkle a bunch of group “character” dances (i.e.: the czardash, the mazurka and the polka) into the mix. Swan Lake and Giselle are prime 19th-century models of this convention, popularized by the choreography of Marius Petipa for the Russian Imperil Ballet of St. Petersburg.

“The entire show is about telling the story of each character stripped down to movement.” Beginning with micro-movements, they expanded on the most internal, organic impulses into bigger movements. For instance, in Hamlet’s display of the sword fight, he very slightly puts the blade against his hand and then his throat. “That’s stronger than any saut de basque!” Côté laughed. The questioning moments of these gestures illuminate the meaning of the famous soliloquy where Hamlet contemplates his own mortality.

Relationships between the characters, played out in scenes, use similar techniques, as in the sensuality between Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, and her son—“their lips almost touch.” Laertes’ movement is grounded, attached to the floor, a reflection of his family values. Hamlet, by contrast, is airborne. Côté and Lepage’s research expanded Hamlet’s movement vocabulary into jumps, trying to define metaphor. The contrast in movement language between Laertes and Hamlet defines their relationship as well. The diverse casting is multi-generational, with Claudius in his mid-50’s, Gertrude, a retired classical ballerina, also in her 50’s. Horatio is played by a female, Natasha Poon Woo, in her 30’s.

The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark; Photo by Stéphane Bourgeois

The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark; Photo by Stéphane Bourgeois

Ophelia is played by contemporary dancer Carleen Zouboules, in her 20’s. “The use of micro-movement in her psychological downfall really paid off,” Côté said. “In a sense, we are quite traditional,” he said when asked what makes this show stand out. “Sometimes the most traditional becomes the most ground-breaking.

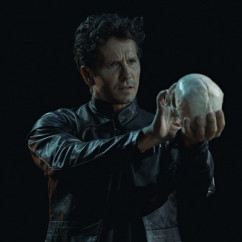

“Underneath the skeleton of Shakespeare’s storytelling, it’s an action play, where Hamlet doesn’t take action. “The skull (“alas poor Yorick, I knew him well”) in the gravediggers scene is incredibly strong!” he said. “It is the skeleton of Shakespeare’s storytelling.”

Hamlet’s duet with Ophelia is “surprisingly effective,” he continued. “It stays away from violence. Her madness is an iconic Lepage moment.”

It was important for them to have original music that would to create a whole world. Canadian composer John Gowsky used an electric hurly gurdy, and electric guitar for atmosphere, and acoustic cello and drums to drive the character of Hamlet. “The music sounds like old music but with modern instrumentation,” Côté added. Each character has its own musical theme.

Lepage works in a trial and error process anchored in the text. The composer was a part of the process. Attending rehearsals, the composer said, the music came to life with the dance. “It’s really a dream to work this way,” Côté said. Experiencing Hamlet on such a purely sensory level frees the audience from having to wrangle with the often obscure language of 16th-century England. “Everyone will understand,” Côté said. “They will walk away having understood the play. It’s a beautiful way to be introduced to dance.” And to Shakespeare!

Renowned Broadway Director Robert Lepage has staged Hamlet numerous times. “It’s a challenge to tell the story without words,” he said in a separate interview with SeeChicagoDance. “Hamlet is the most physical of Shakespeare’s plays. It’s filled with emotion and passion.”

“What’s left when you take the words out?” he posited, then answered himself. “Actually there’s a lot left.” He cites the scene of Hamlet practicing his fencing as the means to express his doubts. “He cuts his finger, questioning with the sword.” Asked how he got the actors to dance and the dancers to act, he said, “Lots of improvisation! It took a few rehearsals for the dancers to understand. You have to be sensitive to ‘accidents’.” He tried to infuse his direction with the particular rhythms of today’s English that define class, social status, and cultural orientation. “The dancer’s body is a poetic thing!”

But it’s not just the actors and dancers who perform the choreography. “There’s a whole “ballet” going on behind the stage action.” It was important that the scenic movement and lighting not overshadow the actor/dancers. “We wanted to tell the story in fresh, contemporary vernacular and yet respect the Baroque way of moving and music. You can be extremely modern by being respectful of the past.”

What would be Côté and LePage’s wish for the audience upon leaving the performance? “For them to walk away saying, ‘We understand!.’ It’s a beautiful way to be introduced to dance.”

“The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark” will be performed November 23-24, 2024 at Harris Theater, 205 E. Randolph, Chicago. Tickets may be purchased at the box office or online through SeeChicagoDance.com or www.harristheater.com.