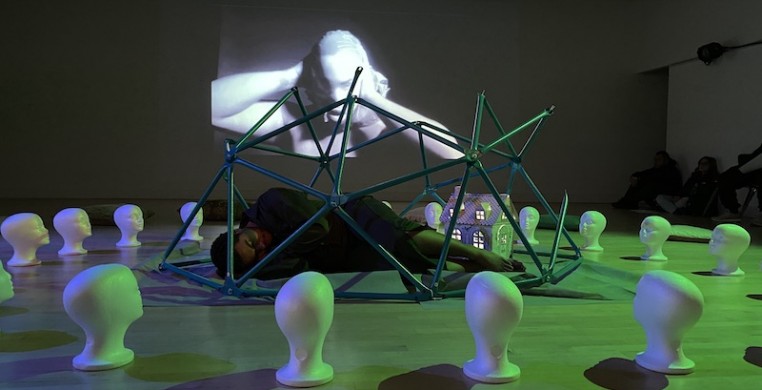

In the program for Anthony Sims’ one-man performance Wednesday at Links Hall, he wrote: “I am placed inside the dome that is constantly being watched, judged and misunderstood. People don’t find black beautiful here. It’s as if my home is in a desolate playground.” I walked into Links Hall’s white box space to find just that—Anthony Sims crouched under a broken jungle gym with a cardboard dollhouse over his head and a circle of white styrofoam heads surrounding him, watching him.

Sims softly shifted beneath the jungle gym, extending his arm, flipping out his wrist and reaching through his curling and uncurling fingers. Inviting us in? Asking for help? Longing for escape?

After recently moving to Chicago from North Carolina for grad school, Sims brought a media collection of previous performance art works and one live performance piece to Links Hall on Jan 8 in “Embodying the Black Experience Through Performance.” The work was durational in that it relied on stillness and observation in two hours of carefully planned, subtle movement mixed with repeating media that brought the audience face-to-face with the perpetual weight and anxiety that minorities in the United States carry. He linked that anxiety back to generations and centuries of persecution through his use of media images, while asking for nothing more than for us to sit and be with him while he reflected on his history and on his current situation as a queer, black man in America.

I was captivated immediately by this image of Sims beneath the jungle gym with broken and disconnected bars, a literal interpretation of his poetic program note made more complex by the other details in the room. Bright lights flashed through the windows of the doll house that Sims took off his head and placed beside him in the jungle gym. Occuring at the same time as Sims’ live performance, video clips and images of Sims’ other performances surrounding themes of blackness were projected onto two walls. Blue and green lighting (designed by Ed Al Tinawi) remained constant throughout the evening, shadowing the white heads and adding changing expression to their faces.

I was struck by the duality of the image he was presenting. On the one hand, he highlighted the beauty in his blackness, with the soft movements of his arms giving off a ghostlike allure as he reached out towards the audience then caressed the iron bars around him. On the other hand, I also saw the space at face value: a figure sitting desolate in a broken jungle gym with an empty dollhouse at his side. Images of Sims with a bird cage on his shoulders flashed on the wall, looking weighted, trapped. It reminded me of Sims at the beginning, with the dollhouse sitting over his head almost like a dunce cap.

The free performance was structured for a fluid audience, with the projected media running on a 10-minute loop, and Sims’ movement staying within the same, somber dynamic for most of the evening. At the door, we were instructed to enter and leave the performance space as needed. The evening began with an audience of 20 people and shifted to an audience of 5-7people for the last hour. Different people came and went, so that by the end it was almost a new audience.

As someone who stayed for the entire two hours, I had a lot of time to think about what Sims wanted me to feel. And it’s interesting being surrounded by different embodiments of the stress, exhaustion and isolation that seems so inherent to a black person’s experience in this country when my history and my experience as a white woman is so different.

In the second hour of the performance, I felt myself drifting from the work. I either wanted to see more from Sims’ live movement or to have an additional media component to experience beyond the short projected loop. I recognize that part of this may stem from my inability to connect with Sims’ story firsthand. But also, I was intrigued by the clips of his other performance art works, and I wish I could have experienced them beyond a 1-minute clip in this space. I vividly remember a video of Sims lying wrapped in a rope connected to a swinging saw above him, where any movement could cause the rope to loosen and the saw to come crashing down. I would have loved to experience this in person or to see a longer video of this in another corner of Links Hall.

That said, the repetitive nature of this performance gave me no choice but to watch Sims and to think about these repeating videos and images referencing segregation and persecution. It brought me beyond feeling Sims’ grief or the torture of black American history or the pain of black American present for two hours on end, and I felt moved to sit with Sims and support him while he felt the weight of these concepts.

Through subtlety and duration, Sims created an intimate connection with the audience, elevating his “home in a desolate playground” to a sorrowful, yet beautiful space of reflection. I hope Sims continues to develop “Embodying the Black Experience Through Performance” during his time in Chicago.