UPDATE: The new seechicagodance.com will launch March 31st. Click here to learn more.

Chicago Tap Theatre presents “For the Love of Tap,” a love letter to tap dancers and fans of tap.

Although Valentine’s Day was nearly a week ago, you can still feel the love—the love of tap dance, that is! Last Saturday evening at the Athenaeum Theatre, CTT opened their 19th season with “For the Love of Tap,” a presentation of the company’s favorite repertory works and some world premieres. Known for their narrative-driven story shows, artistic director and founder of CTT Mark Yonally decided that what tap in Chicago needed this year was a shot in the arm—no pun intended—and put together a program that is light of heart and heavy in rhythm. Yonally was aided by a large company of dancers, returning alumni and a nimble jazz quartet led by the company’s new music director, Ari Burns, and featuring vocalist Leslie Beukelman. Although a one-night-only live event, there will be a digital encore of the performance streaming online from March 4-13.

“The title for this show reflects the fact that for us, tap dancing was one of the things we all turned to, to get us through these times,” writes Yonally in the program, prefacing the opening number. “Just the Two of Us” is a cute, introductory number choreographed by company member Molly Smith and set to the classic tune of the same name by Bill Withers. A string of couples follows each other across the length of the floor, eyes locked, their feet tapping out morse-code rhythmic conversation. Ending in a line, the eyes on the stage turn their attention towards the audience, inviting us to join their world, implying that the “us” in the song is also meant for members of the audience.

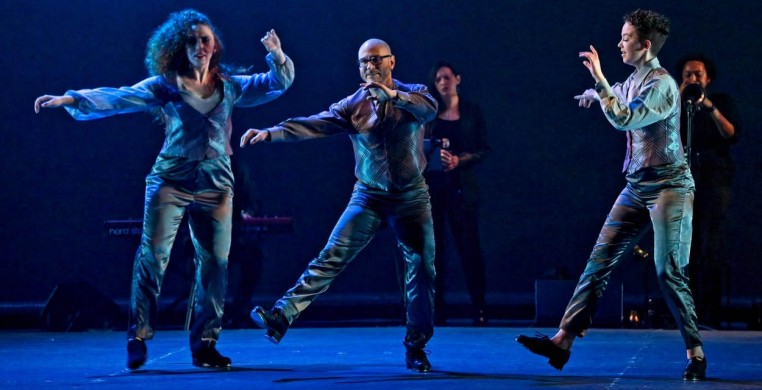

A spotlight shines on choreographer and company director Sterling Harris—literally and figuratively—whose works are featured prominently in the program. Harris’ first piece, “Alfonso Muskedunder,” begins with a single column of dancers, bathed in blue and red lights, pulsing unevenly out to the side, and drawn back in again, creating a stunning 3-D after image effect their feet matching the incessantly fast-paced and uneven drum riff—whack-whack-whack, du-whack-whack-whack, du-whack… They are pulled into various shapes and sizes—a “V” becomes smaller “v”s—and virtuosity is explored through individual solos performed in a semi-circle. Apart from this deviation, there is a constant return to the groove—whack-whack-whack du-whack… “Maiden Voyage,” a premiere by Harris, takes a softer approach to tap. He is joined by dancers Molly Smith and Ally Calamoneri in a trio that rotates through a series of short, light, looping rhythmic sentences, matching in temperance the trance-inducing and dream-like music. Herbie Hancock’s moody, mellow and harmonically rich rendition of a jazz standard of the same name is reimagined by contemporary jazz and hip-hop artist Robert Glasper. Midway through the first act, Harris takes an improvised solo spot to another jazz standard, “Nature Boy,” featuring Ari Burns on trumpet. All alone, Harris resembles a man lost in thought and loitering on a moonlight-drenched street corner at midnight, lashing out at ghosts and breaking free from the constrains of musical meter, endlessly searching, finding it, losing it, and trailing off with a meandering ellipsis—toe, toe, toe, toe, toe… heel, heel, heel, heel, heel…

“Moonlight,” choreographed and performed by Yonally and restaged by Jenifer Pfaff Yonally, features a spritely trio performing to a juxtaposition of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” and Benny Goodman’s “Moonlight Serenade” set against a large projection of the moon in the background. Sweeping legs scrape against the floor as soft arms simultaneously draw circles over their heads and the overwhelming sense of restraint becomes almost unbearable. There is a section midway where the trio slows to a meter-contrasting, 2 against 3 toe-heel crawl that would have given the class act of Coles and Atkins, creators of the “slowest soft-shoe,” a run for their money. In “Moonlight,” the ontological conception of what tap dance is—often portrayed as fast and happy—gets flipped on its head: long, slow drags of the toe are complimented by a symmetrical upper and lower half of the body, a sense that less becomes more, thoughtful and serene. The piece is capped off by a tap-less rendition of Suessdorf and Blackburn’s “Moonlight in Vermont,” featuring the vocal talents of Leslie Beukelman.

“Allied, Unstoppable,” a world premiere by Yonally and restaged by Sara Anderson, opens the second half of the show. The number is big, bright and flashy, and more focused on speed and spectacle than the other works in the program, which are more rhythmical. “Ain’t Misbeahavin’,” also by Yonally, features the duo of Heather Latakas and Sara Anderson and is set to the famous Fats Waller tune of the same name. This piece acts as an homage to tap’s time in vaudeville, quoting various tap dancers popular during the early 20th century, like John Bubbles in a series of heel-dropped counter rhythms, or a backward run in the style of Bill Robinson and even a Cakewalk-esque slide that has the duo kicking their legs at waist level with their torsos leaning back. “Vaguely Americana” is a premiere by CTT alumnus Rich Ashworth and is as much body percussion as it is tap dance, a droning “four on the floor” motif in the heels— doom-doom-doom-doom—lays the framework for the slapping of knees and chests, and the stamping of feet.

Yonally gets his own moment in the spotlight, choosing to share it with longtime collaborator and founder of the Uptown Poetry Cabaret Marc Kelly Smith. In past CTT shows, Smith served as both a co-writer and a narrator, and fourth-wall-breaking interlocutor who spoke directly to the audience. In “Get Set,” Smith delivers a stirring and heartfelt musing that equates love with dance and transforms music into colors. Yonally transforms those colors into sound and movement of the body and feet. The two perform a simultaneous expression of Smith’s prose as ribbons of orange, yellow, green, blue and violet light dot the tops of their heads with kaleidoscopic halos. Duke Ellington’s “In A Sentimental Mood” begins to swell around them. When Smith says, “Oh, hearts leap high!” Yonally springs into the air. When Smith mentions the glances of “señoritas” in a sun-swept Spanish villa, Yonally rolls his shuffling feet outwards and eyes upwards, lips curled into a smirk. “Get Set” is simple storytelling through tap dance and is a solid example of the “tap theatre” style.

The centerpieces of the performance are found at the ends of each act, with a premiere work by tap dance rising “Star,” Starinah Dixon, and choreography by New York-based Brenda Bufalino.

Dixon’s take on Dizzy Gillespie’s “Tin Tin Deo” features the full company and stood out in the program for having a distinct rhythmic clarity. There is a sense of space between each “note” played by the dancers, giving each rhythmic sentence a clear outline and intention. Dixon expertly matches the phrasing of her rhythms to the natural ebb and flow found in the music, having the company get low and go slow, putting their weight in their heels—gang, gang, ga-gang, gang, gang, ga-gang—or getting light and airy, as feet flick out 5 sounds per second during a “wing” step that lifts the dancers off the ground as the music swells towards a conclusion. My only complaint is that the piece ends much too quickly and left me wanting more—I would love to see this piece expanded into a longer work.

“Flying Turtles,” choreographed by Brenda Bufalino and restaged by Kirsten Uttich closes the program. The work, previously set on Bufalino’s own “American Tap Dance Orchestra” dance company, draws on the physical expression of West African movements and pantomime, with music composed by Bufalino and Darryl Grant, with melodic and rhythmic motifs inspired by indigenous American peoples. Fifteen dancers perform starfish leaps on the downbeats, with arms extended and fingers spread, clinging to the edge of a lilting 3/4 time waltz that quickly doubles into a fast-moving 6/8 meter, or a mildly-aggressive 4 against 3 counter beat. The steps are simple. What makes them complex is in how they are assembled, like different sections of instruments in an orchestra, each section fitting in between the notes of the other, all while the company contract their chests and perform sweeping bear hugs, torsos parallel to the floor.

“For the Love of Tap” is more straightforward than a typical CTT performance. It is meant to be an emotional release—a catharsis—as much for the company and its dancers as it is for the audience. “Let’s be honest,” writes Yonally in the program, “the past two years have been tough, and many of us have struggled with fear, uncertainty and loss.” Like CTT’s annual Pride performance, the company tackles an important social issue and chooses not to dwell on the many sad realities, but to focus on the “communal joy of moving together in rhythm and the love that we feel for each other and the art that brought us together.” Judging by the positive response from the audience, I would say that they got the message—and the rhythm—loud and clear.

--

“For the Love of Tap” will stream digitally from March 4-13 on their website, ChicagoTapTheatre.com. Tickets are FREE-$40 and available on the website. For more info, visit the event page below.