UPDATE: The new seechicagodance.com will launch March 31st. Click here to learn more.

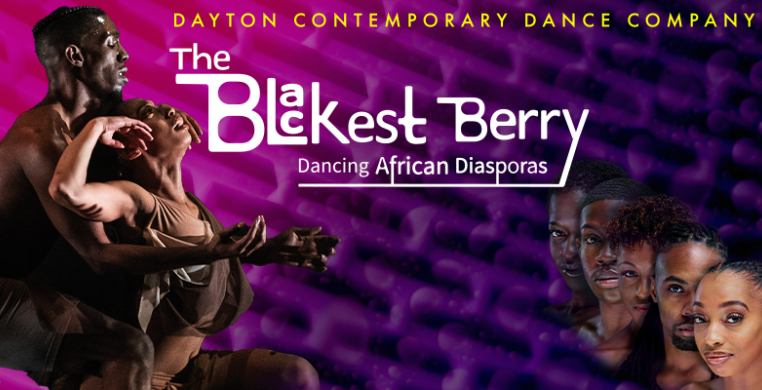

Dayton Contemporary Dance Company presents “The Blackest Berry: Dancing African Diaspora,” May 6.

The phrase “the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice” has taken on different meanings since the first recorded use in the late 19th century. At once a term of affection, more recently the phrase has become a metaphor for how slavery in the United States has affected Black communities, the metaphorical fruit that grew from numerous African ethnicities being forced together through inequality, discrimination and oppression.

Consequently, a four-hundred-year-old Black American culture of art, music, politics, religion and a sense of collective responsibility evolved from the concentrated philosophies and customs of a vast African diaspora. A rich history passed down by the ancestors is now embodied in the latest tour by the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company. DCDC brings “The Blackest Berry: Dancing African Diasporas” to the Athenaeum Center for Thought and Culture on May 6 at 7:30pm.

“The Blackest Berry is about life,” said dancer and Associate Artistic Director Qarrianne Blayr in an interview. “It’s about how we be.” The themes explored in “Blackest Berry” range from historical and political events—like the Middle Passage and the Civil Rights Movement—but also down to the personal level. “Each work has its own feeling, accents and texture,” said Blayr, “but the show overall is about our physicality, spirituality and mentality as Black American people here in the present.

A fan favorite returns in Children of the Passage (1999) by Ronald K. Brown and Donald McKayle, a celebration of past and present cultural rituals set to a blend of New Orleans jazz and contemporary soul music by the Dirty Dozen Brass Band. The piece takes place at an orgiastic party dripping with sin, interrupted when irresponsible actions lead to the death of a partygoer (played by Countess Winfrey). Her ghost returns with a prophetic message: renew yourself by surrendering to whatever you believe in—God, Universe, Spirit. This tale of tragedy and upliftment is told through a combination of classic American Modern and traditional and neo-traditional West African dance styles, specifically Sabar from Senegal and Mali and Manjani steps from Mali and Guinea.

New this season is Home/An Untitled Portrait, by Guggenheim Fellow Tommie-Waheed Evans. Evans investigates how desire, longing, and loneliness intersect through the lens of queer embodiment within Black spiritual spaces. This piece combines American Modern dance with another popular art form of the African diaspora, Hip Hop dance, particularly styles indigenous to Los Angeles, California.

Dancer Quentin Sledge provides insight into how stigmatization and communal bonds are expressed in Evans’ work, saying that “Home/An Untitled Portrait, is a contemporary take on the community experience in L.A.—although it could be New York, Chicago—any place where we are faced with a lot of the “isms” and social challenges—and how we depend on each other to move through those experiences. We see it in fashion and media, people wearing different hairstyles and clothing, things that Black Americans were doing that were deemed unacceptable, are now acceptable because another person outside the community is choosing to adopt Black style and fashion. It feels like a reclaiming of those things.”

American Mo’ by Co-Associate Artistic Director and Princess Grace Honoraria recipient Crystal Michelle features the music of Kendrick Lamar and Duke Ellington. The work pulls from Africana dance techniques and American Modern dance vocabulary and utilizes projections of civil rights marches in the background while dancers in monotone/Earthtone costumes appear and disappear. “It is an ode to the regality and humanity of the time,” said Blayr, “how we would show up to these events wearing your Sunday’s best, dressed to the nines, while our lives were being threatened. It’s displaying your civility, our humanity, even in the face of inhumane acts.”

Rounding out the program is Strong Like We, a work by Katherine Smith that pushes dancers to their limits while paying homage to Smith’s mentor, Mike Malone, cofounder of the Duke Ellington School for the Arts. “It’s less story- driven but is more about community and physicality,” said Sledge. “It’s a very challenging piece and we really do need each other’s support to get through it! There’s a lot of eye contact, a lot of partnering, a lot of cheering each other on from the sides. It’s a representation of how we need community as a practical application where we come together to create this work.”

The rhythm of African diasporic dance is not to be forgotten, and to hear Blayr and Sledge throw out rhythmic lingo would perk the attention of any groove aficionados within earshot. “Very rarely are we on ‘one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight…,” said Blayr. “In each piece there are moments when we flow in and out of the rhythm, over and on top of it.

“We’re rarely on even time,” said Sledge while smiling. “We always play with ‘e-a’ or ‘and, a,’ or stretching the rhythm out, like, if there’s a ‘one,’ we can go ‘ooooooooooone, two.’” From different patterns of breathing to the projected scenery around them, the DCDC dancers live in and have a very intimate relationship with rhythm.

Resourcing hundreds of years of Black history, Dayton Contemporary Dance Company’s “The Blackest Berry: Dancing African Diasporas,” coming to Chicago for one performance only, meshes different experiences of spirituality, from enslavement to today, bonding Black Americans together through trauma and triumph.

-----------------------

The Blackest Berry: Dancing African Diaspora is presented by the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company on May 6 at 7:30pm at the Athenaeum Center for Thought and Culture, 2963 N. Southport. Tickets are $30-$60 and are available by clicking on the event below or by visiting dcdc.org.