The Chicago Dancing Festival is the only free festival of its kind in the nation, and each year, it’s founding directors, Lar Lubovitch and Jay Franke, knock themselves out to give Chicago a full week of the best dance works from the best American and International dance makers and performers. This past week, the tenth annual Chicago Dancing Festival brought five days of free performances by eighteen acclaimed dance companies to five different performance venues around the city.

The intimate space of the Museum of Contemporary Art has been the site of thematic CDF programing focused on an up-close-and-personal look at dancemaking. Last year’s “Modern Women” program at the MCA paid tribute to the legacies of the great female pioneers of 20th-century modern dance and their influence on 21st-century women choreographers.

Fittingly, this year’s MCA program paid similar tribute to their male counterparts in a program choreographed for and performed by men. Even before the performance began, a pre-curtain photo montage situated the program in its historic context of 20th-century male dance pioneers, including Ted Shawn, Charles Weidman, Daniel Nagrin, Eric Hawkins, Donald McKayle, José Límon, Kurt Joos, Harald Kreutzberg, and Merce Cunningham. Once the program began, each of the live performances was preceded by historic film footage of a particular choreographer, leaving it up to the viewer to detect trace influences that might resonate in the performance that followed.

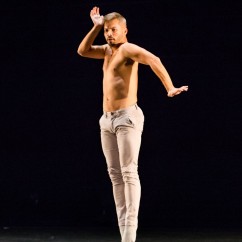

Joshua Beamish’s “Concerto” (2016), his solo visualization of Bach’s Concerto for Violin, Oboe, and Strings in D Minor, recalled the hyper-sensitive expressiveness of Harald Kreuzberg, the German-born protégé of Rudolf Laban, and Charles Weidman, a solo interpreter who also partnered with Doris Humphrey to create a modern dance style built on fall and suspension. Devoid of the dramatic overtones of his predecessors, Beamish’s work is all about the body. Bare-chested and wearing simple white parachute pants, every nuanced articulation of his torso and spine reflected the detailed interplay between music and dancer. It was as if he had no bones, seemingly turning himself inside-out. Sudden reversals of direction and a unique repertoire of squiggles, hiccups, and undulations of arms and legs received Bach’s subtle musical gifts of counterpoint, harmony, instrumentation, melody and rhythm. Interspersed with silken turns and perfect balances were moments of floor work, as when he extended a leg, grasped his toe, balanced impossibly for a moment, and collapsed to the floor, only to rebound to his feet like an instant video replay. Beamish became the animal embodiment of the music in this largely terre á terre phenomenon of technical mastery and musical artistry that somehow combined the ecstasy of total body abandon with the precision of extreme deliberateness. Joshua Beamish

Joshua Beamish

Video footage of Daniel Nagrin’s streetwise common man and an excerpt from José Limón’s “The Moor’s Pavane” preceded Brian Brooks’ duet from “Wilderness” (2016), performed by Brooks and Matthew Albert. The two men were always within each other’s gravity field, much of the time in direct physical contact, engaging and entwining in a symbiotic evolution toward independence. At times, you couldn’t tell where one body began and the other left off, arms, legs, torsos in a constant flow of entwining, folding, unfolding, and reconnecting. The sound score, recorded by Sandbox Percussion, evoked bird-like cries, the sound of subterranean waters, and gem-tones of chimes. Energy flow and its transfer across two bodies mesmerized as it propelled the structural progression of the piece, until its startling finish, as the two bodies separate and come to rest apart, parallel to each other in fetal position on the floor, like newborn twins. Brian Brooks' "Wilderness"

Brian Brooks' "Wilderness"

Film footage of Ted Shawn and a chorus of men connects remarkably contemporary-looking movement to Aszure Barton’s trio, “Awáa” (2012), performed by Jonathan Emanuell Alsberry, William Briscoe, and Oscar Ramos. A program note tells us that “the title means ‘one that is a mother’ in the language of the Haida, an aboriginal Canadian people.” Initially, the men appear in three separate circles of light, isolated from one another. A driving drum beat and repetitive movement evoke a ritualistic feel, the men’s wagging hands and beating feet exorcizing a common demon, or perhaps summoning a common earth mother. The movement is characterized by hip thrusts and loose, almost detached shoulders and arms in a celebratory build, erupting into a kind of vocal hallelujah as they exit dancing. Aszure Barton's "Awáa"

Aszure Barton's "Awáa"

Excerpts from Merce Cunningham’s “Variations 5” played prior to Rashaun Mitchell + Silas Riener’s “Desire Liar (revisited)” (1992). Performed by the choreographers, dressed in red and green jumpsuits respectively, the dancers explored leverage and weight in a kind of random movement laboratory hoisting themselves on, over, and around each other, coupling and uncoupling to the electronic jungle sounds of music by Jesse Stiles. Glen Kotche’s melodic instrumental music shifts the auditory tone in part two with melody and rhythm of pizzicato strings, sending the two into sharp, broken moves that provide more interest with jumps, broad, bold leg arcs, and full-body twists. Desire Liar (revisited)

Desire Liar (revisited)

Donald McKayle’s “Rainbow Round My Shoulder” (1959) remains one of the pivotal social and artistic achievements of 20th-century choreography. The evolution from McKayle’s ground-breaking depiction of a southern black chain gang to Rennie Harris’s signature work, “Sudents of the Asphalt Jungle” (1992) was the most direct connection of past to present on the “Modern Men” program. A voice-over of Martin Luther King and the African drum music of Goodmen would seem to signal a politically-charged arena all about the struggle for racial equality in America. Instead, we enter an urban world where African American men celebrate their freedom, cultural inheritance and identity through a uniquely explosive dance form that pays homage to its African roots with the distinctly American athleticism of hip-hop and virtuoso break dancing. That this dance form has travelled from Philadelphia’s inner city streets to the concert dance stage is testimony to the power of art to transform society. As pure entertainment, it is irresistible for the sheer brilliance of the dancing, infectious musicality, and performance brio of the dancers. But of course it’s a lot more than mind-boggling head spins, flips in the air, hand-stands and grand stands. It’s about the solidarity and pride in identity that all of us can see in these effervescent dancers. Students of the Asphalt Jungle

Students of the Asphalt Jungle