Ron De Jesus’s “The Osiris Legend” premiered in its only Chicago performance at The Ruth Page Center this past Thursday. The production, a Chicago/Detroit collaboration, was performed at The Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts in Detroit the following Saturday.

A choreographic story of epic proportions, “Osiris” brings to mind Martha Graham’s modern dance innovations using Greek mythology to explore the psychological drama of the human condition through the art of dance. Like Graham, De Jesus’s movement invention and overall production design are inspired by the pictorial art of the myth’s cultural derivation, in this case, ancient Egypt, creating a kind of living hieroglyphics. But make no mistake, there is nothing derivative about his choreography.

Ron De Jesus Dance, recently relocated to Chicago, staged an impressive first Chicago concert a little over a year ago. “Osiris” gives further evidence of this choreographer’s unique voice and rich well-spring of movement ideas. “Osiris” is a theatrical tour de force that tackles the daunting prospect of full-length dance storytelling with vigor and freshness, but not without a few issues which deserve attention and adjustments.

First, what is most wonderful about “The Osiris Legend” is the keen movement portrayal of each of the principal characters. Their interactions reach stunning heights of choreographed family dysfunction that spans the spectrum of human emotion, from passion, tenderness, and devotion to jealousy, resentment, and brutality.

De Jesus frames the complex story of filial love, incest, and betrayal with the character of Alter Ego, danced with marvelous malevolence by Clifford Williams, lately of New York’s Complexions Dance Company. Williams’ long-limbed extensions cast a spell on the space that spanned the entire width and height of the stage. His astoundingly pliable spine twisted and contorted the darkest of intentions and spun them into pirouettes, igniting percussive sparks that shot out through arms, legs, and fingertips.

Alter Ego finds his principal target in Osiris’s emotionally volatile brother, Set, danced by Joffrey Ballet’s Christian Denise. While Williams’s Alter Ego is all evil, De Jesus draws a multi-layered portrait of Set, and Denise delivers Set’s compellingly tormented psyche with conflicting qualities of fidelity and jealousy, lust and hatred, through bold strikes, squared-off arms, flexed feet and powerful elevation. I couldn’t help thinking of Iago in Joffrey’s recently-staged production of Lar Lubovich’s “Othello.”

Oscar Carillo’s Osiris, in stark contrast to Set and Alter Ego, is all about beauty, wonder, adoration and undying love. Exciting lifts and the sheer joy of boyish athleticism capture the camaraderie and filial devotion of brothers in his initial duet with Set. Carrillo, a 2015 apprentice with Hubbard Street 2, is a dancer of disquieting beauty, with a heightened sense of poetry in his statuesque carriage and elegant directness. De Jesus capitalizes on his innate lyricism with the legato lines of longing arabesques, soaring arcs, and torso undulations.

Cole Vernon’s impressive characterization of Horus, the revenge-seeking son of Isis and Osiris, prepares for war with Set, his father’s murderer, with sharp, slashing attack, angular knees and elbows, thrusting arms, barrel turns and combative arial twists and dives.

De Jesus is spectacular at male-to-male face-offs. Each duet—Alter Ego infecting/instructing Set; Set bonding with and later betraying Osiris; Horus fighting Set—and the final, thrilling trio between Set, Alter Ego, and Horus are marvels of movement invention, tearing open the essence of human conflict and the struggle for dominance. Catapults, lifts, counterbalance, and the sheer push-pull of bodies responding to the impulse, weight, and shape of each other’s movement create emotional tension that tells the story directly. And the recurring choice of percussive music throughout these particular segments is the most affecting correlation of visual and auditory imagery of the entire piece.

Less unique is his depiction of the women, their interactions with their male partners and with each other. Both Shauna Zambelli as Isis and Lizzie MacKenzie as Nepthys are lovely dancers portrayed in more general terms as lyrical, feminine, and sympathetic. Their ceremonial decorum, with dips and bows around each other, and their elegant partnering in pas de deux with their respective brother/husbands, are poignant, almost symphonic in visual harmony, but lack the specificity of the male characters. Musical choices may be in part responsible for their seemingly passive roles.

There are three spell-binding exceptions. The first instance is the trio between Set, Alter Ego, and Isis, in which Alter Ego casts a spell on her, transforming Isis into a sleepwalking specter. This most beautiful sequence is not only aesthetically riveting, but amps the suspense of the story as De Jesus pitches us headlong into the dramatic climax.

The second, is Set’s abuse of Nepthys when she discovers what Set has done and defies him. De Jesus paints her emotional shift in a solo of disillusionment, with her arms rubbing across each other over her pelvis to the sound of rushing water, as if she were drowning in a sea of anguish.

The third is Isis’s painstaking retrieval of the dead Osiris from the sea. Watching Isis wrap his lifeless form in a foil shroud, and then lift the foil mold from his body, is practically heart-stopping. Here, the simplicity of her methodical, seemingly dispassionate movement stands out in relief against the dire and desperate circumstances to create emotional truth of the highest order.

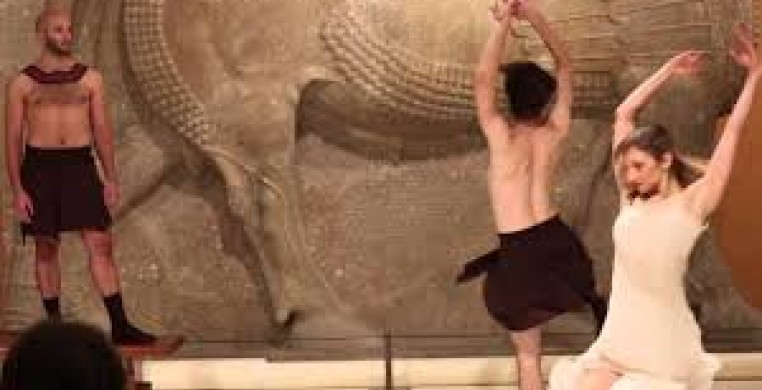

De Jesus’s strong costume choices of bare-chests, metallic collars, and Egyptian kilts for the men, and simple slitted gowns for the women, coupled with the streamlined functionality and visual economy of his set design, contributed to an appealing production style that was not always paralleled by the music. Some sloppy splicing is an easy fix, especially the ending, but a patchwork of many musical idioms, some a bit busy, did not always serve the beauty and design of the choreography. This estimable ballet deserves better visual/auditory collaboration.

For instance, at times, the grand orchestral proportions and overly-sentimental melodies of Mahler overwhelm the simplicity of Isis and Osiris’s movement. Their interaction speaks for itself and needs no musical commentary to illuminate its meaning. The music also prolongs a good-bye scene that accomplishes its purpose halfway through the music. Judicious splicing could help, but a simpler orchestration and musical structure might underscore the scene more effectively. Perhaps a commissioned score might be worth pursuing down the road, music that compliments the sophistication of the choreography, including replacing the clichéd, 1930’s B-movie Egypt-sounding curtain warmer.

One last nit-pick: the program promised an intermission between Act I and Act II, but that never occurred. An uninterrupted hour and forty-five minutes is too long to go without an intermission.

The overwhelming strength of a truly engaging evening that was filled with delightful surprises, beautiful dancing, and inspired vision far outweighs the few weaknesses that warrant attention. Let’s hope the auspicious opening night of “The Osiris Legend” will result in further development and a longer stay in Chicago in the near future.