(Continuing in our series, "Write-On Dance: Our Readers Write")

By Hannah Brooks-Motl and Ingrid Becker

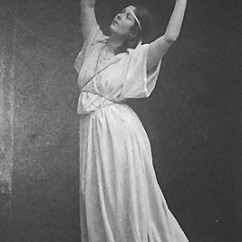

It started, as so many things do, with a Google search. It was a new year of graduate school at the University of Chicago and we were determined not to spend it slumped at our cubicles in the library, forgetting our bodies as we pored over books—forgetting them, at least, until we slung our heavy backpacks on, uncurled our fingers from keyboards, and moved our necks for the first time in hours. We googled “modern dance. Chicago.” As a former Irish dancer and childhood ballet student, we wanted something in between. When we wandered into the Joffrey on that first Saturday afternoon, it was nothing like we had expected. Women of all ages in beautiful silk tunics posed and moved against the bustling backdrop of State Street. That first class we skipped, swayed, and walked. Just walked. To Beethoven’s 7th. Later we would learn that Duncan dancers walk first with the balls of their feet, then their toes. The fingers are relaxed; the whole point is to look effortless, almost ethereal. But as with so much of Duncan what looks easy is really, really hard. Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan died in 1927, leaving behind her a movement philosophy and repertoire that has been passed through generations of students, body to body. We had stumbled accidentally into a secret living history. This history encompassed more than just Duncan herself but everything she drew on, and into, her dance: mythology, philosophy, politics, art. We had discovered a dance form that asked us to think as well as move. And more importantly we had found a community outside the often bleak world of academia. Classes weren’t just filled with beautiful classical music, deceptively simple but intellectually, emotionally, and physically challenging movements and gestures, but also moments of startling connection. As Duncan dancers say, “this is a dance in which we see each other.” We were hooked and going to class became the best part of every week.

Our journey continued, as so many things do, with an email. Our teacher, fourth-generation (that is, three teachers away from Isadora) Duncan dancer Jennifer Sprowl invited us to perform with her company, Duncan Dance Chicago. The rehearsal schedule, given our commitments at school, was intense. But we decided: we were in. And that fall our flirtation with Duncan dance developed into true love. Since then, we’ve learned some of Isadora’s dances, passed down over the last century by dedicated Duncan dancers. Some are playful, lyrical, beautiful (their names say it all): Cherubim. Rose Petals. Three Graces. Water Study, where the dancer is cast as water, bridging the natural world of elements and weather with the human body. Others can be powerful, heroic, even dark: The Revolutionary. Dubinushka (based on a Russian workers’ song). And one of our favorites, The Dance of the Furies, where dancers are vengeful goddesses of the Greek underworld spinning madly, struggling against chains, beating at the gates of hell, throwing boulders, pouncing, and pointing out those who have wronged them.

These dances have helped us explore feelings and sensations too often left unattended to by our daily lives. Duncan technique for instance locates the origins of all movement, all breath, in the “solar plexus.” This is the heart space that we ignore when we slouch at computers, that we collapse with bags, backpacks, and stress, and that Duncan made the center of her dance. The Universal Gesture, a foundational movement in Duncan, involves the dancer bringing the solar plexus down to recognize the earth, to lift and acknowledge the self, and finally unfurl to greet the universe. Earth-self-universe. This sounded… strange to us too at first. But now we do it all the time. And when we show this gesture to others, and invite them to do it as well, the response is always: ahhhh. Why? We think it’s a couple of reasons. Duncan dance recaptures many things lost in our contemporary moment. When we dance we look each other in the eye, call to each other—moments of contact we usually perform, if at all, on cell phones, computers, screens. Duncan is truly a dance of embodied emotion, communion, and exchange. And the other reason our friends, family, students, and the occasional brave professor like doing the Universal Gesture? It just feels good to open your arms, your throat, your chest to the sky. Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan

Ingrid Becker is a PhD candidate at UChicago, where she works on the linkages between poetry and the social sciences. Hannah Brooks-Motl is the author of two poetry collections and a PhD candidate in English at UChicago. Both are ensemble members of Duncan Dance Chicago.