The Last Link

“My life is an open pamphlet.” Bob Fosse

We all know Bob Fosse was a Chicago boy, a Northsider born and bred; and we claim him as our own. There aren’t many people around town who knew him before he was “Bob Fosse.” But there is still one last DIRECT link to Bob. This link grew up with him and knew him better than anyone else, his vaudeville partner, Charles Grass. Both born in 1927 during the last Roar of the Roaring 20s, Bob would have been 90 in a few weeks and Charles will be 90 in December.

Bobby and Charlie met at the Chicago Academy of Theatre Arts when they were about seven years old. Bobby began coming to the Academy with his sister, Patricia. He told Charlie he was taking dance lessons because he had had double pneumonia twice and they thought a third time would kill him. His parents hoped dancing would strengthen his lungs. Charlie began tap class when he was about four and a half. His parents had seen Bill Robinson at the Lincoln Hippodrome, right before he was born, and decided if they had a son he would tap.

Brother acts were all the rage and the Director of the Chicago Academy, Frederic Weaver, an old time vaudevillian and professional musician, thought to try a pint-sized version. He paired Bobby and Charlie—one blond and one brunette—since they were of a similar age and build and looked as if they could be brothers. They became the “Riff Brothers,” all three choosing that name, since the boys excelled at tap riffs. They always made all their own decisions concerning their act— as they did that first time when they were eight years old—by playing rock /paper/scissors! Bob Fosse, 6 months before he entered the Navy

Bob Fosse, 6 months before he entered the Navy

Margarete Comerford, their teacher at the Chicago Academy who had been a professional dancer with the Tiller Line and Joe Frisco, choreographed basic routines for them. As they grew physically and in ability, they added to them. There were plenty of old fashioned “In-The-Trenches” and “Over-the-Tops” as well as winding-the-clocks, moxie-fords, swat wings, toe-stands and knee drops. Bob loved knee slides but they were a “no-no” as far as Mr. Weaver was concerned! An eleven minute Flash Tap Act, the Riff Brothers ended their act with good-natured competition dance steps with double eagles, barrel rolls, pendulums and pull backs. Charlie was more balletic and Bobby was more athletic; together they were terrific! “Our routines would be considered intermediate or perhaps advanced intermediate today,” Charles says. Those routines would become the basis for Bob’s future work on Broadway and in film.

The Riff Brothers spent time together outside the studio as well. They fished at Garden Lake—Bob liked to catch Blue Gills with a bamboo pole--ice skated at Rainbow Gardens and took vacations at Island Lake. They were young boys, each other’s best friend, acting their age when they weren’t dancing. Bob and Charles at Riverview Park, 1944

Bob and Charles at Riverview Park, 1944

Charles tells the story of a studio recital when they were about ten. Charles chuckles, “We were doing a ballet routine with both of us in white, poufy shirts and grey tights. Some boys in the back of the audience were laughing at us during the performance. As we got off stage, we agreed we should beat them up. We threw on pants, chased the other boys around the block until we realized we were still wearing our poufy shirts!”

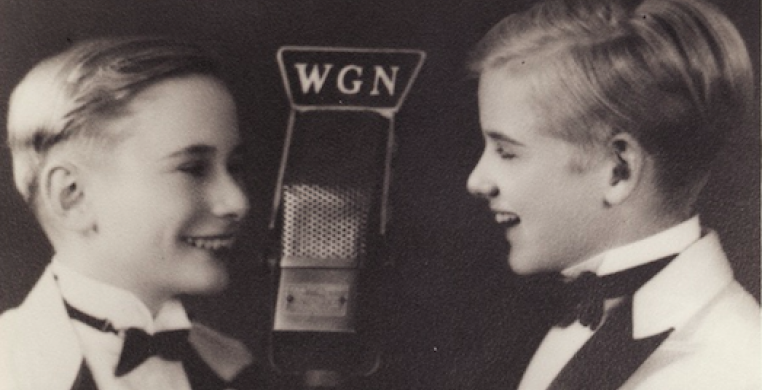

The Riff Brothers became professionals at the age of 12, making the Midwest vaudeville circuit, as well as dancing in many vaudeville theaters in Chicago. They danced for the USO at Great Lakes Naval Base, the Field House at Fullerton and on stage in Ganz Hall in what is now the Chicago College of Performing Arts. On a radio talent show they came in second to a tap dancer standing on his head, and they had a great time as the “Twin MCs” for their dance school’s recitals. Bobby and Charlie, age 15, as "The Riff Brothers"

Bobby and Charlie, age 15, as "The Riff Brothers"

They also danced in some unsavory places, top burlesques houses of the day, such as The Silver Cloud and The Cuban Village. They came dressed for those gigs in everything but their coats and shoes because the only place for them to change was the Men’s Room—and those were disgusting! With Charlie’s mom, Marie Grass, as their chaperon, they spent the time the burlesque dancers were on stage in her Ford doing their Latin homework.

Bob was the youngest of six children and his mother had heart problems, so Mrs. Grass took her chaperoning duties seriously. “Ma was sweet as pie but tough as nails. Bob respected her opinions, often asking her to take a look out front at a new step he was working on,” Charles remembers. They lied about their age—they were 15 when they should have been 17—and worked every weekend, earning in two days what others made in a week.

Bobby and Charlie were taught by Fred Weaver to follow these rules: “There is always someone better than you. Take something old and make it new by putting your own spin on it. Be nice to the people you meet on your way up; these are the same people you will meet on your way down.”

Charles believes Bob kept those values until the day he died. Charles has imparted that same wisdom to his six children and six grandchildren.

“The experiences Bob had in the ten years we performed under the guidance of Fred Weaver as The Riff Brothers can be seen in his work where you least expect it,” Charles says. “The low ceilings in the Kit Kat Klub scenes in ‘Cabaret’ were reminiscent of the low ceilings we hated because we couldn’t jump when we performed in Rathskellers.”

When Charles first saw “Chicago” on Broadway, he almost fell out of his seat when Jerry Orbach appeared as “Billy Flynn” on stage. “He was a dead ringer—moustache and all—for Mr. Weaver our personal manager and seemed to be an homage to him,” Charles believes. There were subtle in-jokes and one-liners Charles understood immediately throughout the show. In the lyrics of “Cell Block Tango,” two of their favorite in-jokes—Lipschitz (Bob thought the name of his high school classmate was funny) and Cicero (they were never to take a gig in that town) are repeated and repeated; it was Bob making fun of Bob. There is more Chicago in “Chicago” than anyone would realize. Charles often says about Bob, “You can take the boy out of Chicago but you can’t take Chicago out of the boy”--or the mature artist. Charles and Ruth Page in "Harlequin," Chicago Grande Opera Balet, 1948

Charles and Ruth Page in "Harlequin," Chicago Grande Opera Balet, 1948

Charles life was different from Bob’s-- he was married to the same woman until her death, three weeks before their 60th wedding anniversary-- but it has been a life filled with dance nevertheless. Charles was Ruth Page’s assistant for four years, dancing and going to Broadway with, “Music in My Heart,” as her assistant choreographer. He was stage director for several Chicago opera companies and a national officer for NADAA (National Association of Dancers and Affiliated Artists), teaching tap, ballet and character dance around the country. He became a ‘teacher’s teacher’ forming a national dance teachers organization, ‘Take 5 Workshops,’ along with fellow Chicagoan, the late Tommy Sutton. Charles and Rose Marie at their 50th Anniversary

Charles and Rose Marie at their 50th Anniversary

Marie Grass Amenta studied ballet and character dance at Stone-Camryn School of Ballet. She attended the Chicago College of Performing Arts (Roosevelt University) as an undergraduate and for graduate school and was the graduate assistant to the Chair of Music Education and Director of Choral Studies. Currently, she directs a semi-professional chamber choir in the south suburbs of Chicago, gives pre-concert lectures as well as writes program notes for various performing arts organizations in the south suburbs and writes a weekly Blog entitled “Choral Ethics” for ChoralNet, the online community of the American Choral Directors Association.